How Much Should Your Backpack Weigh on a Thru-Hike?

How Much Should Your Backpack Weigh?

There’s a lot of information and helpful advice out there, but the truth is that pack weight is highly specific to the individual. Your own frame and figure, individual needs, and preferences all factor into how much weight you can (or should) carry. Besides, you’re the one who’s going to be hauling the stuff, so it’s up to you what all goes in your pack.

That being said, there are some general guidelines that can help you determine the upper limits to how much weight you can comfortably carry.

A common backpacker’s rule of thumb is that a fully-loaded pack shouldn’t weigh more than about 20 percent of your body weight. This means that if you weigh 150 pounds, your total pack weight should fall at or under the 30-pound mark.

Photo via Nika Sturm.

Base Weight vs. Pack Weight

A 30-pound base weight is typical for traditional backpackers—but what does that mean, exactly? When hikers refer to the weight they’re carrying, they’re referring to one of two things: base weight or pack weight.

Base weight is the weight of your loaded pack minus any consumables like food, water, and fuel. The amount—and weight—of these items fluctuate over the course of a trip, so they aren’t included in base weight. We only factor in items that are constant in weight, like your water filter and sleeping bag.

Most hikers aim for a base weight under 20 pounds, while a base weight under 10 pounds is considered ultralight.

Pack weight is what your pack actually weighs on-trail, including all consumables. This number fluctuates and will always be higher than your base weight—unless you come into town running on empty, which (arguably) isn’t the best situation to find yourself in.

Factors That Affect Pack Weight

There are a number of factors that can influence both your base weight and pack weight.

Food

What is a hiker without food? Hangry, probably. If we could, we’d all probably carry more of it. Because it weighs a lot though, it’s important to be conscious of what kind of foods we pack. If you can, try to stick with food items that are lightweight and calorie dense—a good rule of thumb is to aim for at least 100 calories per ounce.

Mmmmmm.

Trip Duration

The longer the trip, or the longer the stretch between resupplies, the more food you’ll need to carry. Yay! More snacks, but also more weight on your back… Try to follow the advice above and keep in mind that your pack will steadily get lighter with each thing you eat.

Clothing

We’re not dressing to impress here—we are hiker trash, after all. Pare down your wardrobe to include only what you need.

Exception: Cold/foul weather gear: Can be heavy and bulky, but necessary. Consider the season and the type of climate you’ll be hiking in. Are you hiking during shoulder season? At altitude or during monsoon season? Plan accordingly.

Season

Your pack in winter will likely weigh more than your pack in summer because the cold weather necessitates extra clothing, a warmer sleeping bag, and (potentially) specialty gear like microspikes or an ice axe.

Age of Gear

Backpacking gear has gotten steadily lighter throughout the years. By no means is this an attempt to put anyone down for carrying an OG pack that’s been faithful through the years. It’s probably going to be heavier than most of the options that are currently out there, but if you’re OK with that, then carry on by all means.

Some of Earl Shaffer’s gear from his 1948 AT thru-hike. Hopefully none of your gear is quite that dated… Photo via Joe Harold, taken at the AT Museum.

Price Tags

A lot of newer, lightweight gear out there can often come with a higher price tag—but it doesn’t necessarily have to. If you’re in the market for a lighter pack or other gear, take your time and do your research (and hit up those holiday sales).

Amount of Gear/Supplies

It may seem obvious, but many a hiker has fallen for this one. Avoid this pitfall by going on at least one shakedown hike before setting off on your bigger hike. This is a great way to figure out what works for you vs. what doesn’t and sort out the stuff you thought you needed from what you actually needed.

Take the time to go through each item in your pack and ask yourself—what purpose does this serve? If you have a hard time answering the question, it’s possible you might not need it as much as you thought.

Luxury Items

Certain items may not serve a critical purpose, but they might bring you joy—and that can go a long way on-trail when energy or morale are low. For instance, maybe you wouldn’t dream of parting ways with your mini air pump because you just can’t stand the thought of blowing up your NeoAir yourself. Just try to limit how many luxury items you bring along and be mindful of their added weight.

Are Crocs your luxury item? Photo courtesy of Emran Kassim.

Packing for Your Fears

Realistically, you can’t plan for every single worst-case scenario, so limit your gear to what you actually need. That applies to food and water, too—while running out of these things is a valid concern, you don’t need multiple days’ worth of extra rations. If the section of trail you’re on has plentiful water sources, you probably don’t need to lug around multiple liters of water, either.

The more you know…

It’s highly likely that you’ll make some edits to your gear list over the course of your trip, especially if you’re hiking a long trail. You’ll probably send home some stuff that you realized you didn’t need and/or end up making some swaps for lighter, more functional gear. The good news? Your pack will most definitely get lighter as you dial in your gear.

Gear photo via Emily Sharplin.

How Low Can You Go?

Ultralight backpackers can go down real low—with their base weight, that is. We’re talking a sub-10lb base weight here, which undeniably, is pretty impressive. As we’ve established though, the number doesn’t matter so much as long as you’re comfortable and able to enjoy yourself out there. But if you’re uncomfortable and you’re not living your best life…well, that matters quite a bit.

There are a growing number of backpackers who believe that achieving the lowest possible base weight is the way to go. Whether or not that mentality resonates with you, ultralighters have a point—there are some advantages to toting a lighter pack.

Photo via Owen Eigenbrot.

If you’re arriving to camp at the end of each day with excessive soreness and pain in your neck and back, it might be time to consider lightening the load. Here are some things to consider:

Pros of having a lighter pack:

- Increased comfort. How are you supposed to enjoy yourself if you’re constantly in pain?

- Less stress on your joints. Why not make things a bit easier for your knees and ankles? This one’s especially important for long-distance backpackers.

- Necessary for physical/medical reasons. Hikers of smaller stature may actually require lighter, smaller packs. It’s not that they’re not strong, because they are—it’s that whole don’t exceed 20 percent of your body weight thing. Certain hikers may deal with medical conditions, like a bad back or knees, etc. A lighter pack really is necessary here.

- You can travel faster/longer. This is especially appealing to long-distance hikers. If you can hike faster, you can get to camp earlier and/or take more breaks throughout the day. With a lighter pack, you might find that you have enough energy to go a little further.

- Less top-heavy. Toting a larger, heavier pack can mess with your balance or agility when navigating tough sections of trail. Think loose scree, washed out trail, deadfall, sketchy river crossings…

- Less to keep track of. Don’t underestimate the joy of minimalism. Less stuff means fewer problems.

Cons of having a lighter pack:

- Fewer luxury items/items in general. You might have to leave behind the mini air pump or that cute dress you like to like to wear on town days. In all seriousness, you will have to be more strategic with what you include in your gear kit, luxury or not.

- $$$. More often than not, newer, lighter gear will cost you. This is where it’s super important to do your research ahead of time and make your new gear purchases during sales, if possible.

- Can come with a learning curve. It takes time and experience to figure out what works for you and what doesn’t. When you make the switch to ultralight gear, you may find that you have to practice setting up/using the gear properly, i.e. trekking pole tents.

- Have to be more careful. It’s no secret that lightweight gear is made with lightweight materials. Depending on the material of your new gear, you might have to be more careful with it. This is especially true for whisper-thin ultralight rain gear or other gear that can be easily snagged on brush.

- Not suitable for cold weather. Even a winter pack can be made lighter with a modicum of restraint and an investment in quality gear. But if you’re heading to the mountains in the cold season, you’ll probably have to let go of your ultralight dreams in the interest of safety.

Lightening the Load

If you’re interested in lowering your base weight, start small. You don’t have to spend oodles of money on an all-new, ultralight backpacking kit right away—or ever, really. Being strategic with your upgrades will go a long way.

Before you start, make sure you know your current base weight. You can get an inexpensive digital luggage scale that will help you easily weigh each piece of gear. Remember: base weight is the weight of all of your gear except for consumables.

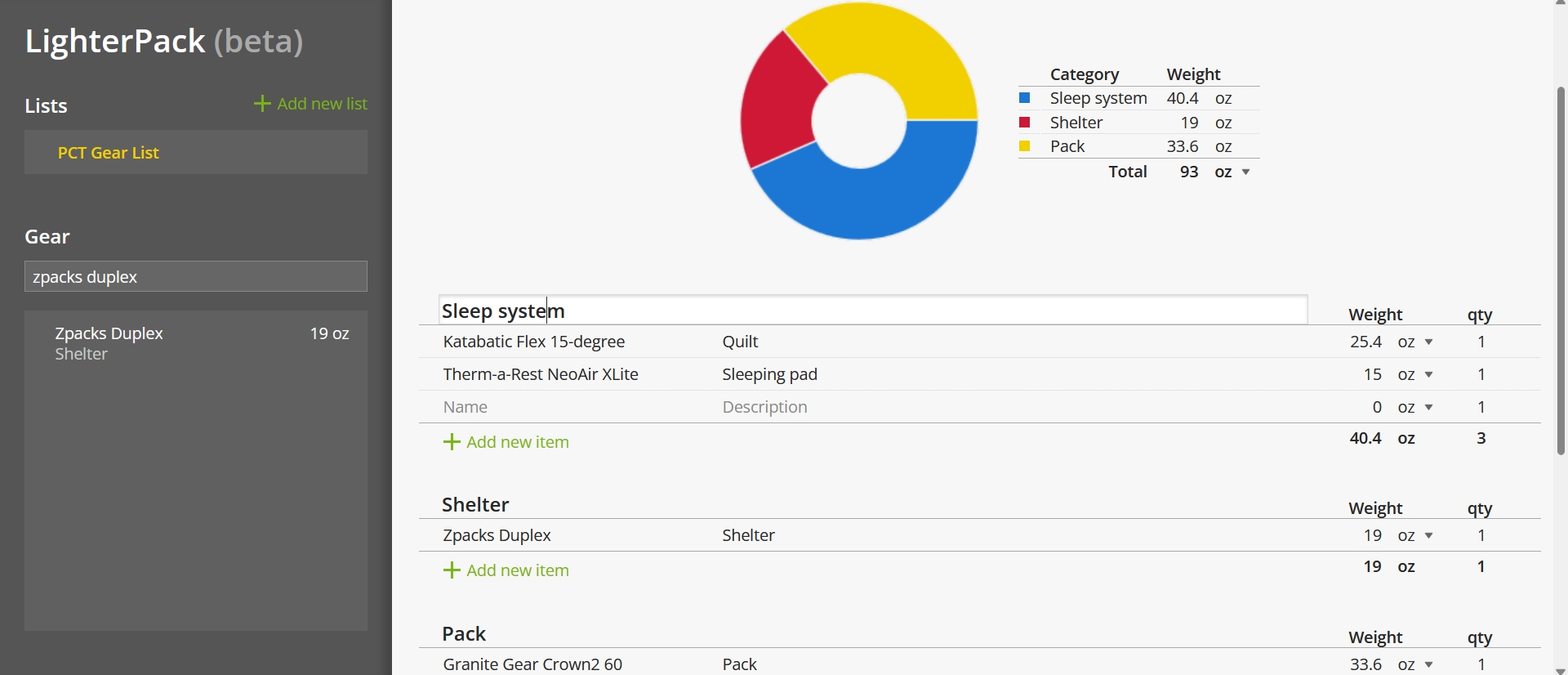

You can keep track of all of this by using a free online resource called LighterPack. With LighterPack, you can itemize your gear, keep track of your pack weight, and even share your packing list with others. Cool, right?

Now you’re ready to start strategically upgrading your gear. Start by focusing on the bigger stuff first—aka the Big Three. Of the three, start with your sleeping system (pad + bag/quilt) and shelter. Aim to get the weight of your sleeping system and shelter down to three pounds or less each.

Once you’ve upgraded those items, then you can start looking for a lighter—and smaller—backpack. Because you know the weight and volume of your sleep system and shelter, you’ll have a better idea of which pack size you need.

If you don’t want to start from scratch, we’ve already compiled lists of the best thru-hiking sleeping pads, sleeping bags, tents, and backpacks for 2023, all of which were largely based on data from our annual Appalachian Trail thru-hiker survey.

Then comes all the other stuff: your clothing, cooking set-up, water filtration system, first aid, and smaller things that will hopefully bring you happiness on-trail. Don’t sweat this stuff as much—upgrading these items is all good and well, but they’re lower priority than the Big Three.

Photo via Katie Kommer.

Tl;dr

If you didn’t read a single thing up until this point, then remember this: backpacking is all about getting out there and enjoying yourself. When it comes down to it, all of the talk about base weight and lightweight this and ultralight that is really just about making sure that backpacking is as fun as possible.

Photo via Brian Garner.

Keep these four things in mind:

- Aim for a 20-30 pound base weight. If yours ends up being even lower, then good for you! You’ve probably invested a lot of hard work and time in getting to that point.

- Have fun 🙂 If you think the weight of your pack is taking away from your fun, see if you can lower your base weight. Remember, the more experience you get over time, the more you’ll be able to dial in your gear. When you make upgrades, remember to start small and spend money where it matters.

- Use your resources. Your fellow hikers and the internet are great resources! Whatever your predicament is, you’re probably not alone.

- Touch some grass. Literally. If you find yourself overwhelmed by all of the resources out there on this subject, unplug for a bit and head outside. That’s what we all love to do best, right? Remember, what all of this comes down to is making sure that your backpacking experience is the best it can be.

Comments? Feedback? Feel free to drop a line below.

Subscribe to The Trek’s newsletter to stay up-to-date on all things hiking-related.

Featured image via Owen Eigenbrot.

This website contains affiliate links, which means The Trek may receive a percentage of any product or service you purchase using the links in the articles or advertisements. The buyer pays the same price as they would otherwise, and your purchase helps to support The Trek's ongoing goal to serve you quality backpacking advice and information. Thanks for your support!

To learn more, please visit the About This Site page.

">

">

Comments 12

I disagree, “This number fluctuates and will always be higher than your base weight—unless you come into town running on empty, which (arguably) isn’t the best situation to find yourself in.” It is the best situation. It means you have not carried any excess to your next re-supply.

And I disagree with Jhony. Cutting it that close on food with no margin for unexpected events is unnecessary risk.

I agree with Pinball, being that low is a huge risk. When I hiked the Long Trail I was a day late to resupply and was on empty. We used the extra days ration and think I was down to one granola bar by the time we were out. Only time I was that low on rations.

I also agree with squirrel and pinball. I cut it too close on the Florida trail 2023 with just one slim Jim and one power bar after that was gone for lunch now I had no dinner one day out for resupply. I came on a small campground and a nice couple made me two pb&j wraps and I ate one for dinner and save the second one for the 15 mile walk to my next resupply the following day.. I did not like that feeling of having no food..

Do you count your basic worn clothing as part of your base weight/pack weight or don’t really include it?

Worn clothes is not included in your base weight.

What the heck are worn clothes?

I think it takes at least 2 or 3 shakedown hikes before I am able to dial in my base weight and resolve some of my crazy ideas of what I actually need on the trail for specific conditions.

Crocs (or any camp shoe) seem to be the thing most discarded in hiker boxes and are 100% unnecessary IMO. If crocs seem like trail luxury, my definition is very different. At close to a pound in weight, I can give a whole list of other luxury items I’d rather have at much lower weights. An extra pair of dry socks comes to mind immediately.