Red Rock Country: What Locals Wish You Knew

“There are two easy ways to die in the desert: thirst or drowning. This place is stained with such ironies, a tension set between the need to find water and the need to get away from it. The floods that come with the least warning arrive at the hottest time of the year, when the last thing on a person’s mind is too much water.” -Craig Childs, “The Secret Knowledge of Water”

Warning: There are lots of pictures in this post because this place is awesome.

My intention is to share pictures and convince you to visit Southern Utah, but more specifically to share tips and tricks from locals about how to have the best time and stay safe. This is an incomplete collection of local advice and I’d like to thank the owners, staff, and patrons of Willow Canyon Outdoor Company in Kanab, Utah for letting me “interview” them. Here’s a link to their website. https://willowcanyon.com/

The Red Rock Country of Southern Utah is high desert at 5,000 feet, and is sometimes called Color Country or Canyon Country. It’s known for its wide open views, hoo doos, arches, red rocks and sand, mesas, bluffs, as well as wave-like slick-rock, and slot canyons. Its beauty is astonishing, sunrises and sunsets are magical, and the landscape can make you feel like you’re on another planet. Mars maybe.

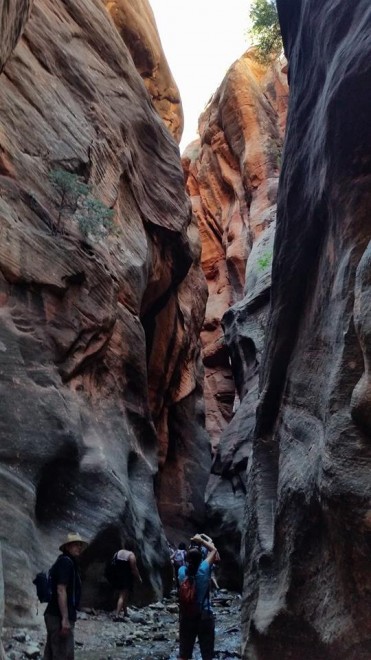

Hikers traverse a red slick rock section on the trail to the Subway, a slot canyon in Zion National Park.

Why should you visit Red Rock Country?

You’ll never see anything quite like this region anywhere else in the world, and there is no way to appreciate the vast space and scale of the landscapes out here until you experience it for yourself. Stand under an arch or a waterfall, be dwarfed inside giant alcoves, frolic with bunnies among riotous wildflowers, take pictures of blooming cacti in the spring (but don’t touch!), see pictographs and petroglyphs, find broken pottery and petrified wood in the sandy washes, explore ancient cliff dwellings, touch dinosaur tracks, hike to world famous destinations, rappel into slot canyons, climb to the top of bluffs and mesas for views into forever, see naked geology-in action, learn ancient history, swim in creeks, rivers, and lakes, including Lake Powell. You might just fall in love with Red Rock Country as have millions of visitors from all over the world, and your friends might even enjoy your slideshow when you get home.

So, what do the locals want you to know?

Do your research!

1. Get permits ahead of time.

If you want to see the Wave, or hike the entire Narrows, or the Subway, or backpack the Paria River you need a permit for these and many other hikes. Google is your friend in finding the appropriate organization to contact to find out about permits. If you are hoping for a walk-in permit, have backup plans ready, because in the summer there can be 150 or more people in the lottery for 10 walk-in permits for the Wave. By fall of 2015 there won’t be any more walk-in permits for the Wave anyway. It will all be online.

2. Check the weather reports for your trip.

Check multiple sites for every area you plan to visit, and check every day so you can adapt as needed. Check the weather the morning before you leave on your hike, and then watch the skies anyway. Things change fast out here. You must pay attention to the weather no matter what the weather report said.

3. Consider visiting Southern Utah in the shoulder seasons and winter instead of during the heat of summer.

In many opinions May, September, and October are the best months to spend in the high desert near Kanab, Utah, but don’t be surprised by the crowds. Winter can be hit or miss with the snow and ice, but with over 300 sunny days a year, if you have crampons, trekking poles, and like to hike in the sunny cold, you might find winter is your favorite time to visit. The Bryce Canyon hoo doos are even more impressive with layers of snow highlighting the pink rock segments. In the winter you can snowshoe and ski in the higher elevations of Bryce and at Brianhead on Cedar Mountain. Remember that the North Rim of the Grand Canyon is closed from October 15 through May 15. You don’t have to bother with shuttles in Zion in the winter, so it’s a great park to visit in the “off” season.

4. Go up in elevation to escape the heat.

If you do visit Southern Utah in July, consider going up in the mountains. Cedar Mountain has a wildflower festival every July but at 10,000 feet it can hail and snow on you even in July. Bryce Canyon and the North Rim of the Grand Canyon are all up in the 8,000 foot elevation range so it’s cooler (I hate heat and would never enter the Grand Canyon in July but the rim has some fabulous hikes and views).

5. The monsoons are coming.

The monsoons come in July and August and they can ruin all your plans, or cool things off and enhance your experience depending on your plans. Expect thunder, lightning, hail, humidity and wind, and bring rain gear. Most deaths from drowning in the desert happen in July and August due to flash flooding. Be ready to change plans if you get a slot canyon permit in July or August, depending on the weather. Often the storms hit in the afternoon, so start early and be out of danger zones (low lying areas, washes, slot canyons, etc.) before afternoon.

6. Buy and carry the relevant paper maps and a compass (National Geographic made new maps to cover our area and they are great).

Getting lost can be deadly out here. Study the terrain and climate ahead of time (use your Google skills!). Even without a compass, being familiar with the region and what to expect can save your life.

7. Rent a four wheel drive.

When renting your vehicle ask yourself this question. What’s the difference between All Wheel Drive and Four Wheel Drive? Answer: getting stuck and not getting stuck. Rent a four wheel drive with high clearance if you intend to do any off-road travel, and many of the coolest places are off the paved road. Four wheel drive vehicles have a lower gear ratio, better tires and better suspension to travel miles and hours out on Hell’s Backbone road or Cottonwood Canyon Road or any of the deep sand roads out to White Pocket in South Coyote Buttes. Make sure you have a spare tire or two and get insurance on your rental.

8. Consider hiring a guide, at least for your first visit.

The cost of hiring a guide company with their super vehicles and knowledge of the region could easily be worth the expense. Plus they know all the cool spots nobody else will be going to, and you’ll have a unique trip that you don’t even have to plan. If you want to go into Antelope Canyon, you’re required to hire a guide.

9. Don’t go on dirt roads in the rain.

They’re often clay and four wheel drive won’t help you stop on slippery clay. Flash floods can cross the road and trap you on the wrong side of where you want to be. Keep extra water in the car (five gallons is good), plus enough snacks and supplies, including blankets or sleeping bags, for everybody to spend the night in the vehicle if it gets stuck or slides off the road into a ditch or as you wait for the flood water to recede (don’t drive through flood water crossing the road).

10. Especially if you’re hiking/traveling alone, leave information about your destination, route planned, number of people in your group and your approximate intended return time with somebody so you have a chance of a rescue in time.

You can leave the info with the hotel front desk, or with family back home that you can contact. Give yourself a few hours leeway, or even a night, depending on the type of trip, so SAR isn’t called out when you’re just running late. Keep your phone charged so you can make contact in case of emergency, or to let others know you’re fine. Consider carrying a Delorme InReach or a Spot transmitter.

11. Ask the locals about road conditions.

Once in town ask advice (such as at the local outfitter or tourism office) about the condition of roads, slot canyons, and trails. Certain areas are better depending on the weather and some roads can be dangerous or closed due to flooding, mudslide damage, or fires. Plus, if they like you, a local might take you to their special, favorite, secret spot after swearing you to secrecy. You never know, it could happen if you’re charming enough.

12. Zion National Park is amazing in the rain and the winter.

The roads are paved, most of the trails are paved, sudden waterfalls can pour over the cliff walls in a beautiful and unique display, the colors of the rocks and flowers are enhanced in the rain, but all slot canyons are unsafe in the rain. Don’t enter slot canyons when the chance of rain is 20% or higher.

13. Start hiking early in the morning.

Before daylight is good, especially if you have a drive before your arrive at your destination. Try to be done with your difficult or exposed hikes or at least heading downhill by 11:00 am. Rest indoors or in the shade during the hottest part of the day and resume outdoor activities in the cooler evening hours.

14. Wear appropriate footwear.

Please don’t try to hike to the Wave in flip flops or climb Angel’s Landing in high heels. People do this all the time and it’s ridiculous. Chacos, Tevas, and other sporty sandals can be great, depending on your hike and personal preferences, but bring moleskin, alcohol wipes, sports tape and other blister treatments. If you don’t prevent the blisters early, you can buy supplies in town later, when your feet are raw meat from the sand in your shoes. Remember there are snakes, scorpions, cacti, barbed wire, and deep, hot sand out here, so consider that when choosing footwear.

15. Don’t skimp on your first aid kit.

Sort through it before you go out. Make sure your iodine wipes aren’t dried out, bring tweezers for cactus spines, scissors, electrolytes, coban/vet wrap, large bandages, triple antibiotic, etc. Your first aid kit is not the place to cut weight in the desert. I consider whiskey part of my first aid kit after I used it to sanitize a deep barbed wire scratch when my alcohol wipes were dry. Oh yeah, are you up on your tetanus shot? Not a bad idea, either.

16. Know your limitations.

If you have a heart condition, maybe you don’t want to plan a rim to rim Grand Canyon hike in the middle of the summer. If you’re claustrophobic you might not want to enter a slot canyon called Fat Man’s Misery. There are all sorts of adventures for every level of activity and fitness. Choosing the right activity will make for an amazing visit.

17. Bring a flashlight or headlamp and a lighter.

Just wrap the batteries in duct tape, keep them out of the headlamp until you need them, throw it all in a dry bag or ziploc, drop into a pocket in your pack, and hopefully you’ll never need to use them. Since you’ll be doing late evening hikes because it’s cooler, you may find that having your headlamp allows you to extend your hike, or get back to the car safely and without worry. In an emergency, light is precious.

18. Don’t crush the cryptobiotic soil.

It’s alive, and it’s really, really old. If you’re off trail and run into a patch of this unique looking soil back up and go around, rock hop, or step in deer or cattle prints. Please don’t step on, ride your bike through, or especially tear up this special soil with ATVs.

https://geochange.er.usgs.gov/sw/impacts/biology/crypto/

A few easy ways to die in the desert.

An incomplete list of ways you can die or at least get your plans ruined in the high desert, and some solutions so you can have a better trip and don’t meet the search and rescue teams, who are awesome people but possibly you’d rather not meet while they’re on the job.

1. Dehydration.

Solution-carry and drink at least 1 gallon (4 liters) of water a day. More if exerting yourself in the sun or climbing. Camel up in the morning by drinking at least a liter before you start hiking, so you can carry slightly less water weight. If you are a bigger person, you need more water than a gallon a day and since water weighs just over 2 pounds a liter/quart, plan to carry at least 8 pounds of water for each person. Don’t expect to just find water in the desert, or to be able to drink the water you find without filtration and treatment. Don’t rely on water sources to be available, even if they’re marked in your guidebook. It’s a good idea to carry some form of water treatment on your day hikes in case anything goes wrong and you (or someone else) end up needing more water than you brought.

The Subway in Zion National Park. Don’t drink slot canyon water unless you are dying, because it might kill you.

2. Hyponatremia, aka electrolyte imbalance.

Solution-eat plenty of salty snacks throughout the day, and add electrolytes to all your water after the first liter. I got hyponatremia on the Appalachian Trail in Virginia in June in 2012, because I hiked all day in the full sun, drank 6 liters of water, and didn’t take any electrolytes or eat enough salt. I was very ill, and still have a low tolerance for heat three years later, so don’t let this happen to you! It can kill you.

3. Drowning. Flash floods are deadly.

Solution-know the weather report and check it as often as possible if you are going into slot canyons, washes, or drainages, which you probably will, because that’s why people come to this area. Don’t enter a slot canyon if it’s raining on you or within 50 miles, especially upstream or around drainages that feed your slot canyon or river. Since that’s hard to know, a good rule most locals follow is to not enter a slot canyon if the chance of rain is 20% or higher.

This video shows a hiker debating entering a slot canyon in Southern Utah (hint-he shouldn’t have), and shows how beautiful slot canyons can be, and then shows the flash flood which trapped him overnight.

4. Heat stroke/heart attack.

Solution-wear a hat that covers the back of your neck, and loose, lightweight, light colored clothing to keep the sun off your skin. Wet the clothing as often as you can, while still saving enough water to stay hydrated. Seek shade for the hottest parts of the day (11:00 am-4:00 pm), and do all your hiking early or late in the day when it’s cooler.

A local man recently got his truck stuck in deep sand as he drove around looking at old archeological sites on side roads. He was missing for several days before they found his body, still holding the shovel he’d been using to try to dig out his truck in the heat. That week temps reached at least 110 degrees Fahrenheit and the assumption is that exertion in the heat was too much for his heart. Remember that even if the temperature says one thing, when you get out in open sand or on open slick rock with no tree cover, it acts like an oven and the ground bakes you from below as the sun bakes you from above. Combine high heat and something like getting lost or car trouble and you could die. Hike early!

5. Lightning strike.

Solution-be aware of storm clouds in the distance and get off exposed areas. Don’t shelter under the tallest or only tree on an exposed bluff or trail. Caves/rocks are not safe in lightning storms because they conduct the lightning. Don’t lie down, the ground also conducts electricity. The less of your body touching the ground the better. Move 50-100 feet away from companions so if one is struck it doesn’t jump from person to person. Get out of water when thunder and lightning are present.

Monsoon season is usually July and August and that can mean daily thunderstorms complete with hail, thunder, and lightning. In 2013, three people were struck by lightning at LeFevre Scenic Overlook near Jacob Lake on Highway 89A. Two of them died and the boy was revived and survived. The storm was miles away.

6. Falling.

Solution-use marked trails, be aware of undercut trails and boulders and cliff edges, watch your feet, especially while taking pictures. Don’t back up towards the edge of a giant cliff, not even to get pictures. Don’t be a jerk and pretend to fall off cliffs to freak out other people, either. People fall and get injured or die all the time out here. I know of many incidents, most of them fatal.

Angel’s Landing and Observation Point in Zion National Park have information boards at the beginning of the hike warning of the dangers of falling and listing the number of deaths from falls from those trails. People fall and die in the Grand Canyon all the time. You could Google plenty of stories. It’s easy to get ledged out (trapped) while hiking and scrambling around on these massive bluffs and people make mistakes while rappelling, too. A man died just last week after falling into a canyon in Zion. He was about to rappel, and was on the edge of the cliff, but wasn’t roped in, not even with a safety. He fell and died. Don’t be too casual with heights.

7. Hypothermia. Yes, you read that right.

Solution-always carry a rain jacket, poncho, or emergency blanket in your pack. Not only can you use it in the monsoons, but the plastic can be used to collect rainwater in an emergency. It also makes a good wind block.

Why would one worry about hypothermia in the desert? Being too cold? The temperature can drop more than 30 degrees from daytime to nighttime temps. Add in thunderstorms with hail that get you and your gear wet and night time temps in the 50-60 degree Fahrenheit range and you can become hypothermic. However, the most common time you’ll risk it is in water filled slot canyons. Those pools of water can stay in the 40-50 degree F range and the sun only shines directly into the canyon in mid day. If you’re waiting at an obstacle or rappel in a slot canyon, you’re often wet, trapped in the shade in a wind tunnel and not moving. Many people end up at least mildly hypothermic and then have to swim under partially submerged logs in nearly freezing water. Not fun.

A few years ago there was a group trapped by a flash flood in the Subway overnight, wet, and mostly unprepared for cold or an overnight stay. One of them had to be rescued due to hypothermia while the rest were dropped supplies to shelter overnight. Better to bring your own supplies.

Rattlesnakes and scorpions (honorable mention).

Solution-prevention. If you see a rattlesnake, leave it alone. Use a stick to poke under rocks before you sit on them. Don’t put your hands where you can’t see, especially in rocky areas. Some people wear tall boots, gaiters, or long pants, plus carry a stick to assist with blocking or moving a rattlesnake (though seriously, leaving the snake alone is the best way to not get bit). They tend to seek shady cover in the hottest part of the day, as you should, and come out in the evenings but they follow the ground temperature and can strike out from under a log or rock on the trail in mid day.

I don’t know of anybody who has died from a rattlesnake bite in our area in recent history, but I know of several people and dogs that have been bit and it is disturbing to see the swelling and other reactions. Not something you want to mess with. If you use earbuds while hiking or trail running, try only using one and leaving the other out so you can hear a warning rattle.

This link has all the information you need about rattlesnakes. I edited my post to include this, so go check it out.

https://www.wta.org/signpost/how-to-hike-in-rattlesnake-country

Scorpions are around, but you’re unlikely to see them unless you’re looking under rocks. Shake out your shoes before putting them on in the morning, and a cool trick is to use a black light flashlight at night out in the desert. Scorpions glow neon in black light. Just don’t do it around your tent site. You probably don’t want to know how many are in and under the bushes all around you.

The truth is you’re more likely to die from a bee sting than rattlesnake or scorpion, so bring that epi-pen!

Altitude sickness (another honorable mention).

Solution-stay hydrated, keep your electrolytes balanced, and try to take it easy for a day or two before exerting yourself, plus be aware of symptoms of altitude sickness.

5,000 feet doesn’t seem that high, does it? It can be if you live near sea level, especially when it’s hot and if you get dehydrated. I know multiple people who have passed out, face down in the sand from a combo of elevation and all the other factors in the desert. Bryce Canyon is near 8,000 feet, and the North Rim of the Grand Canyon is a similar elevation. Cedar Breaks is around 10,000 feet.

Enough advice already! These locals sure have a lot to say.

It’s true, but they just want you to enjoy the desert safely, get some awesome pictures, and fall in love with Red Rock Country like we have. What do you love most about the desert? Post your desert tips, tricks and pics in the comments, and enjoy some more of my pictures below.

This website contains affiliate links, which means The Trek may receive a percentage of any product or service you purchase using the links in the articles or advertisements. The buyer pays the same price as they would otherwise, and your purchase helps to support The Trek's ongoing goal to serve you quality backpacking advice and information. Thanks for your support!

To learn more, please visit the About This Site page.

Comments 2

Southern Utah is my favorite. I went to Zion on a family vacation without any prior hiking experience. Observation Point became my first real hike and a tough one at that to start with. The beauty of it is indescribable and no photo can capture just how vast and awe inspiring everything is. So Southern Utah and Zion in particular is the reason I hike today.

My husband sadly did in fact pass away in one of these areas/bluffs after heat/fall. My husband, a veteran, a hero, and an adoptive father loved nature and beauty. The fact that he died there gives me peace to know he was supported with the love of the nature of our Earthly Mother and the spirit of Heavenly Father. He will forever be loved and missed by all who knew him. I am grateful for your place on this Earth as he would have been at peace after seeing your beautiful place, your sunset and your lovely desert. My husband served in 10/11 in Afghanistan before returning home to adopt his niece 1 and raise niece 2 with me. Of course he did not expect to be there- he was on a detour and likely decided to get some sleep up by your BLM land and then got a flat. I am sure he found solace there- He had PTSD and TBIS after injuries down range and was a disabled Veteran. He was our hero! He likely was dehydrated and fell after he was walking off frustration from a flat tire- but if you know you are going- Please research before you go into the desert- and please do all you can to be safe!