Examining the Thru-Hiker Dropout Rate: Survey Results

Ever since Zach Davis wrote Appalachian Trials and started the blog that became The Trek, our purpose has been to help long-distance backpackers reach their goals. In the past, our surveys have focused on identifying the optimal gear choices for Appalachian Trail (AT) thru-hikers. This year, for the first time, we conducted a separate survey on illness, injury, and reasons long-distance hikers drop out before their intended finish point. One hundred and forty-one hikers told us about their experiences. Keep reading to see what they shared, or skip to the TL;DR at the end.

The Trails They Hiked

The vast majority of hikers in our survey had walked at least a section of the Appalachian Trail (AT), and two thirds had completed a thru-hike (walking over 2000 miles in less than a year).

Of those who section-hiked, 21 percent had intended to thru-hike but had not finished, 2 percent hiked the section of the AT that overlaps with Vermont’s Long Trail, and three quarters section hiked for other reasons.

Beyond the AT, participants in the survey had trekked across 27 other long-distance footpaths:

- The Long Trail (16 hikers; some may have been reporting the section that overlaps with the AT)

- The Pacific Crest Trail (11 hikers)

- The John Muir Trail (6 hikers)

- The Florida Trail (6 hikers)

- The Ice Age Trail (3 hikers)

- The Continental Divide Trail (2 hikers)

- The Arizona Trail (2 hikers)

- The Cohos Trail (2 hikers)

- The Foothills Trail (2 hikers)

- The Lone Star Trail (1 hiker)

- The Benton McKay Trail (1 hiker)

- The KATY Trail (1 hiker)

- The Lost Coast Trail (1 hiker)

- The Massachusetts Midstate Trail (1 hiker)

- The Monoadnock Sunapee Greenway (1 hiker)

- The Mountains-to-Sea Trail (1 hiker)

- The New England Trail (1 hiker)

- The North Country Trail (1 hiker)

- The Ouachita National Recreation Trail (1 hiker)

- The Overseas Heritage Trail (1 hiker)

- The Ozark Trail (1 hiker)

- The Pinhoti Trail (1 hiker)

- The Sheltowee Trace (1 hiker)

- South Downs Way in the United Kingdom (1 hiker)

- The West Coast Trail (1 hiker)

- West Highland Way in Scotland (1 hiker)

Hiker Demographics

About 50 percent of hikers who took the survey said they were male, 48 percent were female, 1 percent (1 person) identified as non-binary, and 1 percent (1 person) preferred not to say.1

Hikers were most commonly in their twenties, with fifties and early thirties being the next most common.

Hikers were asked their height2 and their weight3 prior to starting their long-distance trek, and this information was converted to calculate Body Mass Index (BMI). The range of BMI’s was from 17 (underweight) to 54 (obese), with the average BMI being 27, plus or minus 6 units. While the standard measurement puts 27 at slightly overweight, it should be noted that, for this sample, muscle mass likely inflated the BMI calculation for many of the hikers. Still, 27 percent fell into the overweight range, 22 percent in the obese range, and 2 percent in the underweight range.

Pack Weight

We asked hikers to estimate their base pack weight for the majority of the hike (i.e., the weight of their pack with all contents except food and water). We also asked their estimate for their total pack weight when carrying 3 days of food and their total pack weight when carrying 5 days of food.

For hikers who completed the distance they intended, the typical or average base weight for the majority of their hike was 20 lbs., plus or minus 6 lbs. Their typical total pack weight when carrying 3 days of food was 28 lbs., plus or minus 6 lbs. When carrying 5 days of food, their estimated typical pack weight was 33 lbs., plus or minus 6 lbs.

Pace and Distance

The average distance reported for a single long-distance trek was 1418 miles. However, hikes ranged from 25 miles to 5,000 miles, and the majority of hikes described were AT thru-hikes.

We asked hikers how many days it took them to walk the section or thru-hikes they described. Several hikers had walked more than one long-distance trail, so we used the information from the longest trail or continuous section they had walked. Many of them reported in months or weeks instead, so this information is not as accurate. Still, based on their reports of the length of their hikes and the time it took them, we calculated the average pace for thru-hikes, attempted thru-hikes, and intentional section hikes:

- Thru-hikes: 13.7 miles per day, plus or minus 9.8 miles per day

- Attempted thru-hikes: 12.6 miles per day, plus or minus 5.9 miles per day

- Intended section hikes: 11.4 miles per day, plus or minus 5.8 miles per day

Illness and Injury

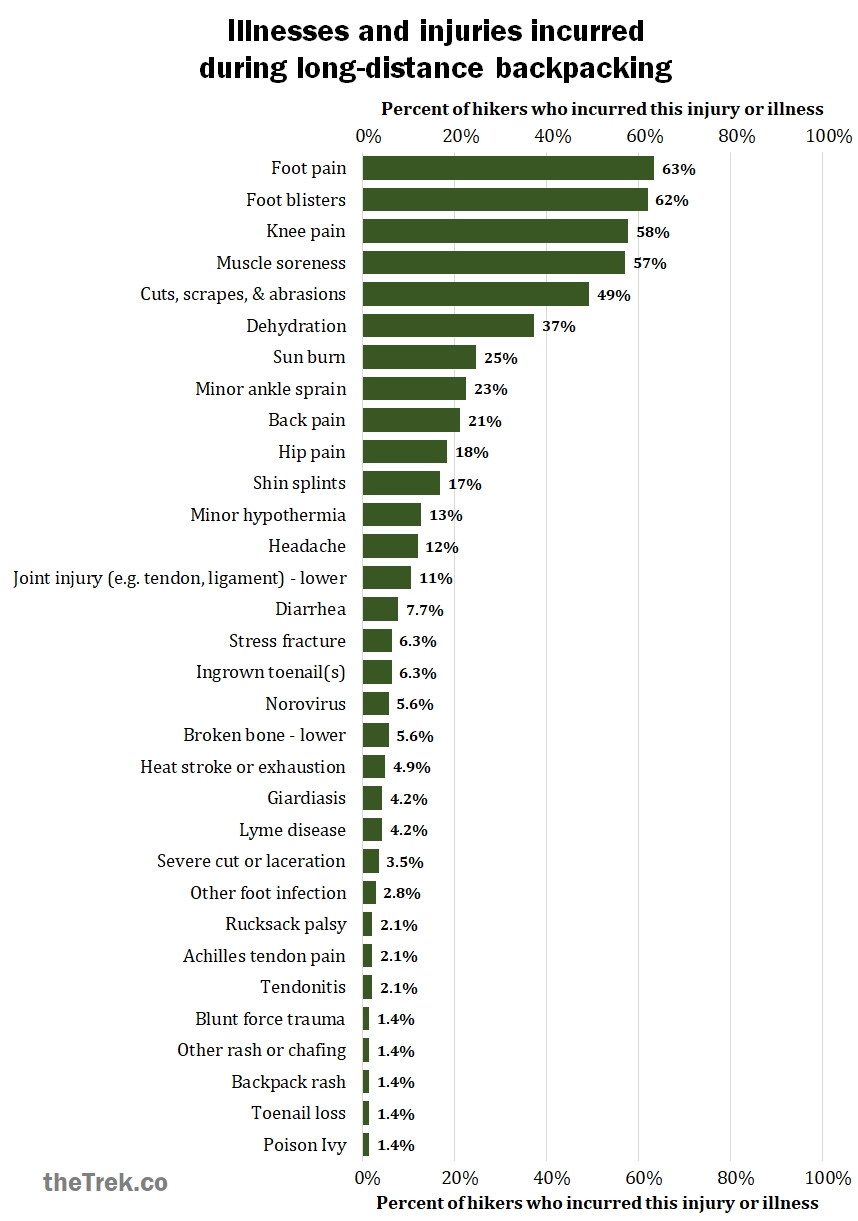

Hikers were asked to check a box for all listed injuries and illnesses they had experienced during their long-distance hikes, and given the option to mention any other illnesses or injuries they incurred.

About half or more had experienced foot pain, blisters on their feet, knee pain, muscle soreness, and cuts, scrapes, and abrasions. The most prevalent severe injury was a joint injury in the lower body (including any severe tendon or ligament problems). Non-specific symptoms like headache and diarrhea affected about 10 percent of hikers, but the most common specific illness was Norovirus, contracted by 1 in 20 hikers. Norovirus cannot be killed by hand sanitizer, only soap and water, so it is more common in the backcountry than in “civilization.” Heat stroke/exhaustion, Giardiasis (“Giardia,” contracted from contaminated water), and Lyme Disease (a tick-borne illness) were about as prevalent as Norovirus.

The following illnesses and injuries (not shown on the graph) were only reported by 1 hiker each: minor frostbite, Plantar Fascitis, upper body broken bone, upper body joint injury (e.g. tendon, ligament), bee stings, Brown Recluse bite, cracked tooth, numbness in toes, numbness in hands, anaphylactic shock, bleeding ulcer, concussion, intracranial pressure, kidney stone, and seizure.

Mental Fatigue

Hikers were asked if they felt they had experienced mental fatigue during their time in the backcountry, then they were asked to rate average typical mental fatigue during the first half and second half of their hikes. 41 percent of hikers felt they experienced mental fatigue during their long-distance hike or hikes.

Mental fatigue was significantly higher during the second half of their hikes, although mental fatigue ratings tended to be low during both the first and second halves of the hike. This trend was observed across thru-, attempted thru-, and intended section hikes.6

Predicting Hike Completion

A major question we wanted to address with this data was which factors predicted hike completion, and inversely, dropping out. Only 66 hikers (47 percent) said they had dropped out of a long-distance hike without completing it (remember, some hikers were reporting on more than one hike, so even though two thirds had thru-hiked the AT, many of these were also reporting on prior attempts or other trails).

Of those 66 hikers who had dropped out of a long-distance hike, their major reasons for ending their hikes fell under the categories of major injuries or illnesses, minor injuries or physical problems, mental fatigue or loss of interest in the hike, and money, time, or family concerns.

Beyond their self-reported general reasons for dropping out, I analyzed whether sex, age, BMI prior to the hike, backpack base weight, mental fatigue, illness, injury, and the distance hiked per day predicted trail completion.7

The following factors did NOT significantly predict whether a hiker completed their intended distance or dropped out: age, sex, distance hiked per day, mental fatigue, and contraction of a major illness.

People were more likely to complete their intended section or thru-hikes if:

- Their BMI was lower prior to the start of the hike (note that only three hikers in the survey were underweight prior to the hike, but about half were in the overweight or obese range)

- Their backpack base weight for the majority of the hike was lower

- They did NOT sustain a major injury

People who completed their hikes were actually more likely to sustain a minor illness/injury (e.g. blisters, muscle soreness, minor hypothermia, headache). Unsurprisingly, the longer a person hikes, the more minor injuries they sustain.

To clarify, based on hikers’ self-report, in many cases illness and minor injuries impact their experience such that they are unable to or no longer want to continue their hikes as intended. Still, our statistical findings show that, in most cases, hikers who sustain minor injuries or contract an illness while in the backcountry are able to complete the hike they set out to do.

TL;DR

- Neither men nor women are more likely to drop out of their long-distance hikes.

- Neither old nor younger hikers are more likely to drop out, either.

- Major injuries ARE a significant predictor of ending a long-distance hike earlier than intended.

- It’s important to note that active individuals tend to have inflated BMI’s due to muscle mass, meaning their BMI number indicates being overweight when they are healthy. Still, almost a quarter of the hikers in this survey fell into the obese range on the BMI, and our statistical analysis showed that having a high BMI predicted ending their hikes earlier than intended.

- The lower a person’s pack weight, the more likely they are to hike the distance they set out to hike. The typical pack base weight for people who completed their trek was 20 lbs., while the typical base weight for those who did not finish was 23 lbs.

- While mental fatigue may increase during the second half of a long hike, general mental fatigue isn’t a significant predictor of completing or dropping out; people who complete their hikes also experience increased mental fatigue as the hike continues.

- In some cases, minor injuries are the main reason individuals do not complete the distance they intend. However, in most cases, hikers complete their intended distance, even as they continue to experience minor injuries and illness the longer they hike.

Thank you!

Many, many, thanks to all 141 hikers who generously gave their time participating in this survey. Additionally, I would like to thank Steven Woods for designing the survey, Maggie Slepian for coordinating the collaboration on this post, Aleta Hegge for designing the title image, and Zach Davis for enabling me to geek out about the mountains.

Notes for the Nerds

- For statistical analyses, we only included the data from people who identified as male and female.

- Height: ranged from 4 ft. 11 in. (1.5 m) to 6 ft. 10 in. (2.1 m), average height was 5 ft. 10 in (1.7 m)

- Weight: ranged from 95 lbs (43 kg) to 346 lbs (157 kg), average was 174 lbs +/- 42 lbs (79 kg +/-19 kg)

- For time reported in weeks, I converted this to 7 days. For time reported in months, I converted this to 30.5 days and rounded up.

- “Plus or minus” refers to the standard deviation.

- Paired sample t-tests were conducted for the overall sample, and then for thru-hikes, attempted thru-hikes, and section hikes. For the overall sample, t = -5.23, df = 134, p < .001. For thru-hikers only, t = -4.17, df = 89, p < .00. For attempted thru hikers only, t = -1.87, df = 8, p = .096. For section hikers only, t = -2.627, df = 35, p = .013.

- A binomial logistic regression was conducted, predicting trail completion. Independent variables entered in block 1 were sex, age, and BMI prior to the hike; in block 2 was pack base weight; in block 3 were mental fatigue in the 1st and 2nd halves of the hike, the minory injury/illness sum score, major injury sum score, major illness sum score, and distance hiked per day.

This website contains affiliate links, which means The Trek may receive a percentage of any product or service you purchase using the links in the articles or advertisements. The buyer pays the same price as they would otherwise, and your purchase helps to support The Trek's ongoing goal to serve you quality backpacking advice and information. Thanks for your support!

To learn more, please visit the About This Site page.

Comments 8

Thanks for putting the survey together. Certainly sounds like you put a good effort into it.

Good information and even more inspiration for finding a way to leave the last couple pounds out of my base weight. Looking forward to an AT thru-hike in 2018.

Hotty Toddy ! Great info! Can’t wait for my first AT experience next spring. I am planning on doing at least the GA portion of the trail!

. . . so grateful for this information. Thank you for taking the time to do the survey analyze and post the results. Very good information.

Some great insight provided here, thank you.

My brother told me about a finding in a different study, they determined the people who completed their intended hike were more flexible in their daily plans. If they were tied or slightly injured they would take the time to slow down or rest. Conversely, those who stuck to a rigid schedule were more likely to quit early and not complete their intended hike.

The information you have given is more on the physical side with only a little on the mental fatigue. While the physical data is very important and will contribute to success or failure, I wonder how much the flexible mindset and other attitudes contribute to success/failure.

That opens up another question, what do hikers consider a success or failure?

The longest hike I’ve done is 60 miles and 6 days on the trail. I have attempted longer hikes but did not complete for various reasons. Some I consider a failure while others I do not consider a failure. Depends on why I stopped.

Thanks again for your study, I really appreciate it.