A Camera as Company: Thru-Hiking in Scotland with a Panoramic Camera

Jet-lagged and running on adrenaline, I arrived at my hotel in Milngavie, Scotland after a flight from the States. A familiar face greets me. Kat and I met while she was thru-hiking the AT last year, and now London-based, she’d taken the train up to meet me for a different adventure. Walking into the hotel and peering behind the counter, a brown box stared back at me with my name written in Sharpie. “I believe that’s for me!”, I say to the clerk. In a thick Scottish accent, she asks for my passport to confirm that I’m the proper recipient.

I gather the nondescript parcel and proceed to my room to organize my backpacking gear and open the box. Camp fuel, trekking poles, tent stakes, food? Nope. Inside were roughly 20 rolls of 35mm film from Ilford, the UK-based and internationally beloved film manufacturer. Backpacking with a camera? Yep. Backpacking with a film camera and THAT MUCH FILM?! I’m a hike-your-own-hike, kind of gal. That night I loaded a roll of film into my Fuji TX1, a camera that shoots panoramic images, returned it to my Hyperlite Mountain Gear Camera Pod, and awaited the journey ahead – the West Highland Way, Ben Nevis, and the Great Glen Way.

Why do I bring a camera on a long-distance walk? The reasons are many, and I’ll do my best to spell them out as I write this. One reason is that it helps me remember the way a place made me feel. I believe every image-capturing device can have a purpose, and for me, shooting panoramics on film during a trek has been a creative and challenging way for me to record the world. I love seeing a moment or place in black and white, I love film grain, and carrying that inevitable extra pack weight has hardly ever bothered me.

About a mile into the trek, I met a man wearing traditional Scottish garb named Alan. We started chatting. He gave me advice, recounted his own walks on The Way, and handed me a newspaper about the 96-mile path. “Can I make your portrait?”, I say. “I’ve had many made, but sure.” he quips. Meter, frame, click. One exposure was all I needed. “Would you like me to send it to you?” I ask. “That’s quite alright, enjoy your walk!”. Another thing I love about taking a camera is meeting and photographing other people.

The West Highland Way travels through many fields of sheep in the first 20 miles or so. Sheep herds are a near-constant sight on this trail. | April 2023

L: Kat walks between sheep fields with a trail marker in the foreground. R: Shadow self-portrait along the same route. | April 2023

After 20 miles of bucolic sheep-covered hills and forestry tracts, we made it to Conic Hill, settling on the hill’s flank. I shot about 4-6 more frames through my camera and retired my gear in exchange for a camp meal and conversation. Conic Hill is notable as a feature on the Highland Boundary Fault, a fault line separating the Scottish Lowlands from the Highlands. Take a minute and look at the photograph I made of our campsite. On the image’s left-hand side, you’ll see how flat the land is compared to the imposing munros on the right of the image. We had now entered the Scottish Highlands.

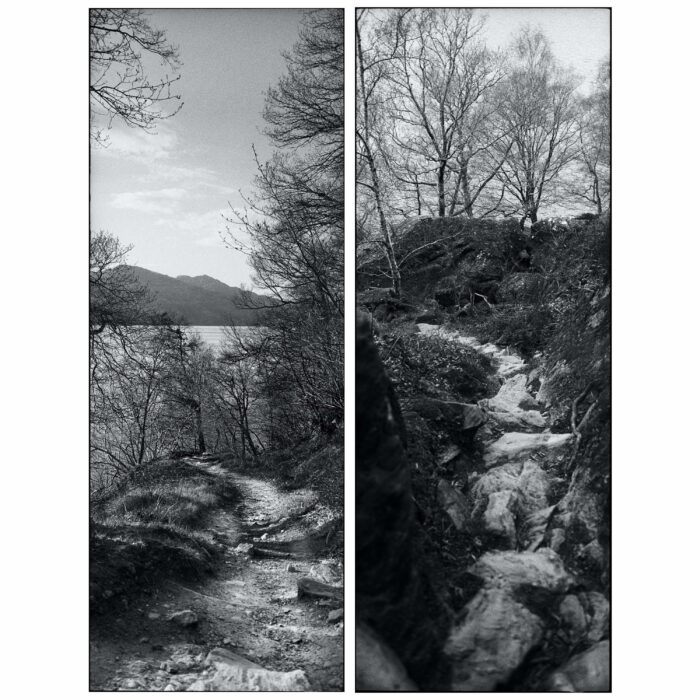

The next two days we’d follow the bonnie, bonnie banks of Loch Lomond. Atlantic Oak forests, single track pulling up and down hills that felt endearingly like the AT at times, occasionally broken up by roads and villages. At a few points, I saw the steep, steep side of Ben Lomond. I envied the walkers who had time to climb this fabled munro. But we were on a mission, and on we pressed.

I’ve been a professional photographer for 15 years, though I take my camera with me on these walks for the sheer love of the craft. I didn’t always feel this way, however. For a number of years, hiking and backpacking without a camera gave me incredible freedom that I hadn’t had elsewhere in a long time – the opportunity to be temporarily relieved of the trappings of modern life.

You may not be surprised to know this, and perhaps you can personally attest to this yourself, but having an “exciting career doing something you love” isn’t free from immense stress and challenges. Sometimes, many times, the last thing I wanted to do at the end of a day was take photos for fun. Last summer, however, I started taking my camera backpacking and fell in love with having my camera along for the ride. A few months later, I did the Grand Canyon’s R2R2R with one of my cameras and a handful of rolls of film, which further reaffirmed how much I was enjoying having my camera with me. Since then, I’ve packed my camera on many multi-day treks and have never regretted it, even when I came home without much in the way of interesting photographs. Because when inspiration does strike, I have my camera.

When Loch Lomond receded, it was as if an old friend and I were parting ways. The oak forests that cradled the trail lessened, and the lands opened up to more heathland. Some distant munros were still snow-capped, signifying both the changes in elevation and in increasingly northern coordinates. That night we’d find a cozy campsite near a burn (Gaelic for a stream), whose sounds made for a pleasant night’s sleep. The next two days brought the wilds of Rannoch Moor and Glen Coe, a feast for the eyes.

Kimchi”, an American hiker walking through Rannoch Moor. Kimchi and I met in the woodlands around Loch Lomond. He lives in California and has hiked large swaths of the PCT, a trail beloved to him.

On our 5th and final night of wild camping on the WHW, we found a hill overlooking the village of Kinlochleven. Day faded, and the village lights provided a kind glow. The next day would be our final push into Ft William, where the northern terminus lies. Because Kinlochleven is the last village before reaching the end, this day was the most crowded, but the scenery made up for any congestion.

My mind was pretty busy between walking, photographing, and what the next day meant – Ben Nevis, the UK’s tallest munro. Ben Nevis is Gaelic for “The Venomous Mountain”. Climbing it without respect can be a death wish. The weather was rooting for us, however, and the Carn Mor Dearg Arete route was looking likely. Before reaching the terminus, I’d see Ben Nevis’ softer side, with its jagged north face hidden from view.

The village of Kinlochleven from above the hills. I enjoyed a fantastic Scottish breakfast here before I began my day’s walk | April 2023

Ben Nevis, the highest mountain in the UK. These hills constantly reminded me that they were once a part of the Appalachians. | April 2023

The original end of the West Highland Way. The current endpoint is a statue in front of a pub. Unless you’re a purist, this is a perfectly acceptable endpoint, as the remaining half a mile or so is just a walk through town/shopping centers. | April 2023

After 96 wonderful miles, 6 incredible days, and 5 restful nights of wild camping, the West Highland Way had come to an end. For me, my ending would be where the hills and wood meet Ft William’s edge. The “new terminus” walks you past shops and ends at a pizza and beer joint, of all places (it is excellent, though).

So here’s where I celebrate. It’s done. If I were to summarize, such a walk felt akin to a hobbit going out on an adventure – wild woods and boggy moorlands surrounded by mountains, buffered by tiny villages stocked with pub food and drink. If one wanted, you could amble from village to village without needing a tent. I do recommend stopping in and getting food and a pint as you walk into towns along the trail. The West Highland Way was a heartwarming adventure through the Scottish countryside, and now, it had come to a close.

The following morning a cab dropped us off at the north face car park, and we began our Nevis approach through a forestry plantation. The Sitka Spruce farm faded, and there it was — Ben Nevis. On a very rare sunny day.

Kat hill walking up Carn Mor Dearg. This effectively pathless munro allows access to Ben Nevis via the Arete. | April 2023

The mighty north face of Ben Nevis, as seen from Carn Mor Dearg. I was so pleased to have witnessed this. Even in the noonday sun, this side of Nevis is nothing short of awe-inspiring. | April 2023

Photography is a funny thing. What a camera is, what a photograph is, what any of it’s perceived value is, varies greatly depending on who you ask. When some people think of photography, they think of iPhone snapshots. Some think of the latest mirrorless system. Some think of Ansel Adams, or massive telephoto lenses seeking out wild bear or moose.

Dear reader, this is all photography. If you desire to take a camera on a thru-hike, I can only encourage you to dig deep and ask yourself this – what are you hoping to explore with your camera companion? Close your eyes, what do you envision? What’s your dream scenario that could be captured because you brought that camera? Snapshots for memories, or something else? By all means, please do serious multi-day shakedowns, make sure you like the camera-carrying method you choose, and get your gear insured, but please – dream a little. See where that leads you in terms of what kind of camera you’d actually like to take.

READ NEXT — Thru-Hiking Photography: What You Need to do it Like a Pro

I was on all fours at times on the scramble, and my camera was for the first time deep inside my pack. Gingerly carting my feet from one boulder to the other, watching for loose scree, I took my time. Kat was ahead, and I needed her to be since she was taking the train back to London that night. We effectively parted ways on that mountain. I was grateful for her company, though now I relished in my own focused solitude.

Eventually, I made it to the top. It felt pretty damn good. I’ve done some scrambling on the east coast and out west that were, grading wise, much more technical than Ben Nevis, but what I found challenging about the CMD Route was that the scrambles are relentless, and there are points where the difference between safety and falling was consistently one loose rock away from one another. It was a route that required 100% focus.

It’s worth noting that there are a number of deaths on this mountain every year by the way. If you’re looking at ascending Nevis, especially via the CMD, be honest with yourself if you do this route. Talk to local guides and mountaineers, consider hiring a guide if you’re feeling unsure, and veer towards being over-prepared. For example, I rented Scarpa boots, crampons, and an ice axe. I ended up really needing the boots and crampons at the summit and for the descent, so I’m glad I had those. Microspikes would have sunk off my shoes in those conditions.

Once I was up there, standing in a field of snow, I looked out to the Atlantic Ocean. I was told that it’s only a few days every year, you’ll be able to see it. The next morning, Ben was covered in his characteristic shroud of clouds. Summiting Ben Nevis reminded me that with informed decision-making and training, I can push myself and succeed; that my mind and body have more to offer than I even realize.

The following day, I set out for the Great Glen Way. Day 8 of walking had me feeling exhausted. My body told me to take a break and I shamelessly made it a nero after 4 miles. I made my way to the village of Banavie and found a bunk at Chase the Wild Goose Hostel. I charged my electronics, took a shower, and marveled out the window at the now cloud-enshrouded Ben Nevis.

The next few days I’d have to push hard to make it to Inverness. The Great Glen Way follows a major fault line that divides the Highlands. It features three lochs (including Loch Ness), all of which are connected via a man-made canal called the Caledonian Canal.

The Canal was finished 201 years ago, and unlike yesteryear when it served as safe passage for cargo ships avoiding angry seas, it now serves largely as a recreation source for canal boats and kayakers. The Great Glen Way leisurely follows the water route, and the walker can expect flat and easy-going canal side walks, and loch-side trails and roads. This route absolutely felt less traveled. It took me mostly through countryside and small villages.

I can’t quite pinpoint it, but what the West Highland Way offered in rugged wild views, the Great Glen Way offered in an incredible window into Scottish country life. Whereas the WHW was mostly full of thru and section walkers, the GGW felt more like a quiet path that served as an artery leading to someone’s sheep field, home, forestry track, path into the munros, and so on. It felt like the epitome of what John Denver sang about in Country Roads, Take Me Home. Watching a farmer on his tractor bringing hundreds of sheep into another field, or watching a canal lock keeper man the locks for boats, having a beer inside a barge, and getting buzzed with local people my age, I felt at home.

Munro with it’s head in the clouds. The Great Glen Way has excellent access to some of Scotland’s finest hill walking. Don’t let the name fool you – hill walking can often be technical and challenging. These mountains ought to be explored reverently. | April 2023

The Great Glen Way alternates between canals, lochs, and forests while traversing the Great Glen Fault Line. | April 2023

A sign indicating directions to Ft William and Inverness. Each town is the terminus of The Great Glen Way. | April 2023

The end of the day came with rain. SNAP. My chest strap broke. I had to laugh a little. Maybe it was the camera bag, maybe it was inevitable wear and tear after a year of heavy use on this pack. A little paracord did the trick and on I went a few hundred feet until I realized I was staring at a barge that was converted into a pub. That settled it. After food and a pint canal-side, I hitched a ride to Saddle Mountain Hostel. So much for camping, now I was having a good time hosteling!

The Eagle Barge Inn near Loch Oich on the Caledonian Canal. The barge is in fact a pub with excellent food and beer. I had a great time hanging with locals here. There are also two excellent hostels nearby. | April 2023

Saddle Mountain Hostel and a field of highland cattle. The sign in the foreground welcomes you to Invergarry. | April 2023

The next morning I had to book it. I was running out of time to finish the GGW. I’d need to walk about 25-30 miles per day to make it in time. Things were starting to feel rushed and even pointless. I felt anxious and kind of down, feelings I hadn’t felt at all until now. I started to consider my options: Push hard, feel miserable, finish the GGW, have your bragging rights. Or, enjoy this walk, take it in, do what you can within reason to make it to a good stopping point, and make your train back to Glasgow on time.

The Great Glen Way is no stranger to road walks. There are plenty to be had, but I found them all to be pleasant. | April 2023

Another pancake flat path along the canal. I loved walking past all of the lockkeeper homes and locks, as seen in the background. | April 2023

A boat waiting to be let through the canal locks in downtown Ft Augustus. Fun fact – people who watch canal boats are called “ gongoozlers”. | April 2023

Eventually, I made it to Fort Augustus. I ate my feelings at a cafe and decided I wanted to prioritize experience over conquest. I could finish the GGW, but I chose not to, and I wouldn’t know what the last 40 miles would be like. But what I did know, was that those 40 miles I had done were beautiful, and I would end by standing on the hills overlooking the famous Loch Ness. There, after descending, would mark the end.

Indigenous Caledonian Scots Pine forest with Munro in the distance. Hundreds of years ago, Scotland was mostly forested with Scots Pines dominating the lands. The forests held boar, bison, wolf, bear, and lynx. Farming and wars have not only extirpated all of those animals, but have brought the mighty forest down to 1% of it’s original range. Now, Scotland’s highlands are considered to be prime land for re-wilding. Time will tell what this means for Scotland’s ecosystem recovery. | April 2023

After a number of woodland miles, I stood atop the high hills with a full view of Loch Ness. I was all alone. Cherishing it, I took a self-portrait and a handful of photographs, and put the camera away. I sat in silence, grateful for such a precious trip. Grateful to my camera for being a fine companion and means to photograph, grateful to Kat for her incredible friendship on the WHW and Ben Nevis, grateful to my fiance Alec for his unending support, and grateful to my body for carrying me. I didn’t have to complete this thru-hike. As it turned out, I had been voraciously extracting the marrow out of life every day this entire time. I wanted for nothing.

While this wasn’t exactly a thru-hike of thousands of miles, those 156 miles were of deep meaning to me personally and creatively. When I told my mother I was nearly done working on this set of photographs, she exclaimed that the photos I showed her were amazing and that the best one I took was a selfie of me at Loch Ness. My mother had only seen iPhone photos of my trip. It made me laugh.

At the end of the day, opinions on photography, cameras, and what someone looks for in a photograph are just as diverse as each of us. I know what I like and what works for me, and what someone else may or may not bring camera-wise is a personal choice. If you take a camera on a thru-hike, I hope it’s one that brings you joy, works hard for you, and is worth every ounce of weight! Eventually, I’ll sell some prints from these images, but I mostly took them because it was in my heart to do so. I love having a camera with me on any long, long walk.

About the Author

Hey, I’m Laura! I spend a lot of my time either behind a camera, outside meandering somewhere, or both. I live in Music City USA but put in a lot of my trail miles deep in the backcountry of the Great Smoky Mountains, where I’m currently working on hiking every mile of trail in the park. The most memorable on trail memory I have was when a bull moose and I almost walked into each other in Michigan. We were both a little stunned. We both survived. My professional work can be seen at www.laurapartain.com or @lauraepartain on socials. My misadventures with moose are not available on the internet.

Featured image courtesy of Laura Partain.

This website contains affiliate links, which means The Trek may receive a percentage of any product or service you purchase using the links in the articles or advertisements. The buyer pays the same price as they would otherwise, and your purchase helps to support The Trek's ongoing goal to serve you quality backpacking advice and information. Thanks for your support!

To learn more, please visit the About This Site page.

Comments 5

Great story and fantastic photos! Thanks for sharing!

Thank you, Dan!

Loved reading this. After having watched countless YouTube videos the written word felt as if my very soul was drifting through the highlands on your journey. As I read “When Loch Lomond receded, it was as if an old friend and I were parting ways” I knew exactly what you meant, I’ve walked the WHW. Fantastic piece of writing and hit the nail on the head.

This was nicely written! Sounds like you had an amazing time.

I’m curious, what kind of training did you do to prepare for the climb? What kind of scrambling on the east coast and out west did you do to prepare for the trip?

Thanks Sarah! Sorry for the delayed response btw. I didn’t intentionally train for the CMD route of Ben Nevis, but I had culminated experiences that gave me what I need to be successful. Old Rag Mountain on the east coast and a few scrambles in the Rockies gave me good experience. I’d recommend learning about the American grading system for climbs/scrambles, and start with Grade 2s, and work your way up. I’d also only recommend working under dry conditions when possible. A big part of it is also developing a sense of how weather conditions affect the terrain/personal safety as well. I’m by no means a climber btw, though I am confident with scrambles. If you’re able to befriend any real mountain climbers (not the indoor climb people haha), that is also beneficial. Between having a mountaineering mentor and starting off with Grade 2 scrambles, I worked my way up into developing a bit of “mountain spidey sense”. I also highly recommend working with guides! Not only can they help you safely complete your climb, but you’re paying to be educated in mountain safety. I would have hired a guide if the weather would have been any less than perfect on Ben Nevis’ CMD btw, or perhaps avoided it. There are also cornices to consider, and if the mountain would have been in alpine conditions (fully winterized and covered in snow), I would have hired a guide. There isn’t a path and there are a million brilliant ways to die on this mountain, so having an experienced guide in deep snow would have kept me say, from mistaking a cornice (snow overhangs that look like a hard surface) for hard rocks beneath. The short – start in dry weather and do “baby scrambles”, meet real climbers and learn from them, and never be afraid to hire a guide!! Remember, guides teach us. Hope this helps to hear! 🙌❤️