When HYOH Does NOT Apply [Part 2]

Every hiker is entitled to hike their own hike up and to the point that it begins to negatively impact the experience of another hiker.

This is, in a nutshell, the core concept behind what it means to “hike your own hike” (HYOH). In Part 1 of this series I discussed one of the more direct ways people can negatively impact the trail experiences of their fellow hikers. However, there is another addendum to HYOH that is not too often explicitly stated. Perhaps because many deem that it should go without saying. In general discussions of HYOH are focused around the social interaction hikers have with each other. Yet, there is one incredibly significant category of transgression that even this hallowed philosophy cannot defend.

When You Compromise the Integrity of a Trail

While HYOH suggests that there is no single “correct” way to hike a trail I don’t think it upholds that there aren’t a lot of wrong ways to do it. Case in point, when you find yourself hiking in such a manner where you risk causing undue harm to a trail or its surrounding environment then you’re doing it wrong.

Why? Because the trails are what make all of this possible. They are the very thing that permit us to have the experiences we seek. They are the chains that link the community together in camaraderie and appreciation. Hiking in such a way where you knowingly compromise these literal foundations of hiker culture is simply indefensible. Period.

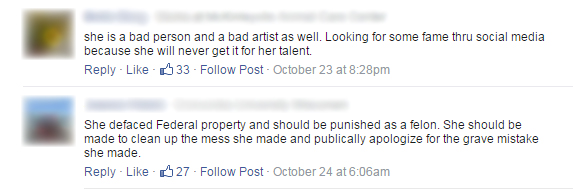

For most hikers this is not something that really applies. Most hiking enthusiasts, particularly long-distance hikers, develop an intimate connection with the trails they choose to travel. It’s why many hikers convey such visceral reactions to those who threaten the trails they love, whether their infractions be intentional or otherwise. So as a result there is really no faster way to make yourself a pariah in the outdoor community than to flagrantly desecrate or harm the trails we all share. Just ask Casey Nocket.

However, we don’t actually have to be doing anything reckless or extreme to cause damage to a trail. The very purpose of a trail is to allow numerous individuals to travel along the exact same path to visit the exact same places. The more use a trail sees the more damage is done. Over time regular foot traffic is enough to inevitably cause issues that require a response. Many trails in America require constant maintenance often carried out by armies of hard-working volunteers to keep them in a safe and usable condition.

The heart of the problem is that much of the damage done to our trails is due to plain and simple ignorance. People often don’t even realize they are causing any impacts on the trails at all. As one of my old professors used to like to say, most people nowadays are “nature illiterate”. If you care to test yourself try looking out your window and identifying all of the trees sitting out in your own backyard? Could you do it? If your answer is a confident and emphatic yes then you’re doing better than most. Pat yourself on the back and get yourself a cookie. You’ve earned it.

Unfortunately there are many out there that can’t complete this task without the aid of Google and Wikipedia. As a society we have let ourselves become incredibly disconnected from the natural world that surrounds us. It’s not something many people seem to think about on a day-to-day basis much less interact with. Such detachment has resulted with the average person no longer understanding the influences they can wield, both positive and negative, on the wild when out wandering on a trail.

So does this mean that damaging acts committed in the name of ignorance are defensible under HYOH. I would argue that no they are not. Simply put when it comes to spending time in the outdoors ignorance isn’t just irresponsible, it’s dangerous. It can’t be tolerated as an excuse. “Hiking your own hike” comes with the assumed understanding that you, in some reasonable capacity, know how to hike in a responsible enough manner that you do not risk the safety of others or the integrity of the trail itself. You don’t have to be a Les Stroud or Jeremiah Johnson, but at minimum you have to understand what you’re getting yourself into before getting into it. It’s as simple as that.

This is where conservationist guides like the Leave No Trace (LNT) can help. Leave No Trace describes a conservationist code of ethics which captures the elements of sustainable hiking/camping summarized neatly into seven basic principles. These principles are designed to allow outdoor adventurers to enjoy the wilderness while minimizing the impacts they may pose. While LNT is not the only conservationist code out there it is easily the most widely accepted and endorsed environmental code of ethics in the outdoor community. The seven principles are fairly self-explanatory and are designed so that even the small child should be able to understand them. You can visit the Leave No Trace Center for Outdoor Ethics to read the more detailed information. In short they break down as follows:

- Plan Ahead and Prepare – Do research! Avoid putting yourself in this kind of situation.

- Travel and Camp on Durable Surfaces – Don’t cut your own path through the woods. Stay on the trail.

- Dispose of Waste Properly – If you packed it in, pack it out. And for the love of , dig a proper cathole.

- Leave What You Find – Take nothing but pictures.

- Minimize Campfire Impacts – Don’t piss off Smoky.

- Respect Wildlife – Don’t poke the bears. Better yet, just don’t poke anything at all.

- Be Considerate of Other Visitors – Don’t be a dick.

Now I’m a reasonable man. I understand that the impact of one single person, on average, is going to have minimal consequence. Yet, we cannot be so facile as to pretend that an individuals actions on the trail can’t contribute to a significant overall impact. Any action, no matter how seemingly insignificant, multiplied numerous times in a localized area can be either incredibly constructive or profoundly catastrophic.

For a prime example of this look no further than the Smoky Mountain National Park–the single most visited national park in the country. Any AT northbounder can attest to stories of the Smoky’s overcrowded shelters, of campsites devoid of firewood due to over-scavenging, or the haunting memories of tiptoeing through toilet paper minefields. The park is in a perpetual struggle to maintain a balance between allowing visitors the freedom to enjoy the park’s unique habitats and keeping the park from suffering irreversible damage caused by the exact same visitors.

A typical shelter in the Smoky Mountains. Camping restrictions force hikers to congregate at designated shelters or campsites throughout the park. So expect crowds in peak seasons. (NOBO’s I’m talking to you.)

I know it’s easier said than done to have a fastidious and uncompromising sense of environmental responsibility. On my own thru-hike I can think of several circumstances where I let my own laziness get the better of me and put my own desires ahead of what was best for the trail. The very fact that we’re human is a guarantee that no one has a 100% LNT success rate. That’s not an excuse. That’s just an unavoidable fact. Still, it is every hiker’s duty, to the best of our ability, to ensure our actions are not causing undue harm to the environments we visit.

It all starts with education. Plan ahead and prepare. It doesn’t matter if you use LNT as your guide or follow some other conservationist code. Before going out into the wilderness or into an unfamiliar environment do your research! Educate yourself! I can’t stress this enough. Read books. Consult other experienced hikers. Do whatever it takes to help you better understand the world you’re venturing into. Do you need to be an expert before you leave? Goodness no, but you do need to know enough to be able to take care of yourself and the trail you travel.

If you’re already a hiking guru than use your powers to help protect that lands you love by working to educate others. It’s true nobody can be forced to educate themselves. It’s particularly difficult if the individual doesn’t even know that they need educating. So spread the word. Create awareness. Remember even small, seemingly insignificant contributions can lend themselves to a greater overall benefit. It won’t just help keep you safe and allow you to better enjoy your experience, but it will help spread the necessary knowledge to aid in preventing irreversible damage to the wild places so many of us love to venture and the many trails that take us there.

This website contains affiliate links, which means The Trek may receive a percentage of any product or service you purchase using the links in the articles or advertisements. The buyer pays the same price as they would otherwise, and your purchase helps to support The Trek's ongoing goal to serve you quality backpacking advice and information. Thanks for your support!

To learn more, please visit the About This Site page.

Comments 4

I apprecate this read, we’ll written and from experience. So, I dealt with another side of Hyoh last year. I met a hiker who was annoying in Monson(sobos). The complaints I have about him place him in the “dick” category. The phrase hyoh came up in VA when he showed up again. It actually took 5 hikers to sit him down to explain why Hyoh was so applicable, he had noro 3 times on trail, puked in at least 3 shelters, and was in constant need of money and food. So my question is. If you have someone who doesn’t know how to hike their own hike, and in incapable of realizing that, how do you deal with it? We stayed in town extra days just to let him get further ahead of us, and we hiked 30 plus mile days to get away, yet he always found us. I realize this is turning into more of a vent, but I wanted to comment. What if Hyoh is bamboozled by someone.