When They Name the Wilderness: A Briefing on Toponyms

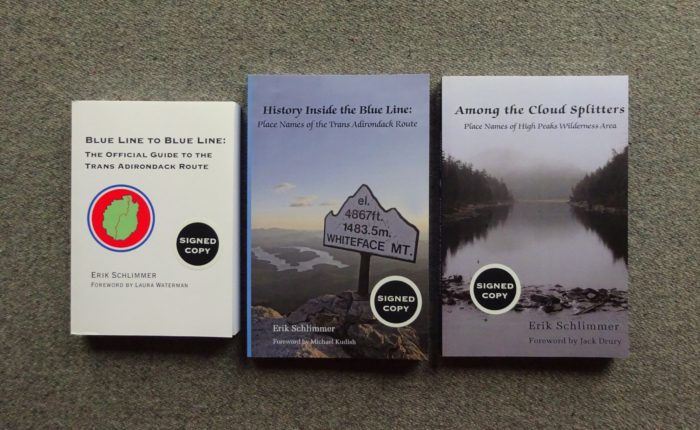

When I was writing a guidebook to the 240-mile Trans Adirondack Route, Blue Line to Blue Line, I shamefully tried to produce a book that guided hikers along this route while discussing Adirondack place name history. That first draft of Blue Line to Blue Line ended up being good at neither. It was like a hybrid bicycle, a bike that stinks on pavement nearly as much as it stinks off-road because it tries to be two things at once. With publication of a trimmed-down version of Blue Line to Blue Line in 2013, I took the remaining place name information I had gathered and wrote History Inside the Blue Line and Among the Cloud Splitters, books solely dedicated to Adirondack place name history. Within these two titles I decoded hundreds of place names—dubbed toponyms—and learned something that only such research could have possibly revealed. That is, behind every name there’s a story, and the story’s usually pretty good.

Yet you don’t have to go to all the way to the Adirondack Mountains to find fine toponyms. Along the Appalachian Trail in New England, for example, there are hundreds of names that likely stem from entertaining stories. Connecticut has Plantain Pond, Sages Ravine, and Wachocostinook Creek. Massachusetts has Saddle Ball Mountain, Walling Mountain, and Depot Brook. Vermont has Glastenbury Mountain, Sucker Pond, and Blind Brook. New Hampshire has Imp Mountain, Leadmine Brook, and Mount Success. And Maine has Moody Mountain, Surplus Mountain, and Mahoosuc Notch. How could there not be entertaining stories behind such great names?

Fear not, for you don’t have to be a researcher to learn toponym history. Folks have been working diligently in this seemingly esoteric field for decades now. For example, Robert and Mary Julyan and Allen Coggins have presented impressive work in their respective Place Names of the White Mountains and Place Names of the Smokies. Other titles are available for other regions of the US. Yet I’m no expert on Appalachian Trail, White Mountains, or Smoky Mountains toponyms. My stamping grounds are the Adirondack Mountains. Therefore, let me humbly share a dozen curious toponyms and their accompanying stories. Perhaps these names will encourage you, next time you hike by Such-And-Such Brook or climb So-And-So Mountain, to take the time to think to yourself, I wonder what the story is behind this name.

Ampersand Lake

Tradition holds that whoever named this lake during the early 1800s must have thought it looked like an ampersand, a symbol—&—meaning “and” and derived from “and per se and.” This theory has fallen by the wayside, especially considering that whoever discovered this lake was perhaps illiterate and probably didn’t even know what an ampersand was. Ampersand Lake illustrates a name corruption. Here, Ampersand is actually “amber sand,” which describes the lake’s bottom.

Calamity Pond

A great “calamity” befell David Henderson at this pond on Sept. 3, 1845. Henderson and a group of men visited this body of water, then called Duck Hole, that day to examine a proposed dam site related to iron production. A pistol he was carrying accidentally discharged, killing him. His closing words were, “This is a horrible place for a man to die.” Then he said to his 10-year-old son, “Archie, be a good boy and give my love to your mother.” The body was carried out along present-day Calamity Brook Trail, which was widened by woodsmen to ease transportation of the corpse.

Catamount Mountain

The eastern mountain lion is known by a half-dozen other names,including catamount, panther, painter, puma, cougar, and wildcat. The name of this 3,169-foot peak may come from a mountain lion sighting that took place on its flanks or summit. Prior to the 1800s, mountain lions inhabited nearly every corner of the Adirondacks. This is evidenced by all such nomenclatures within Adirondack Park: one Catamount (a mountain), one Catamount Hill, one Catamount Knoll, and two Catamount Ponds. Add to these a Painter Mountain, a Panther Hill, a Panther Peak, and a Panther Lake plus five Panther ponds and nine Panther mountains. The last native Adirondack mountain lion was shot in 1908.

Couchsachraga Peak

Pronounced “KOOK-suh-krah-guh,” this name is likely a Native American term meaning “beaver hunting grounds” or “dismal wilderness.” This toponym dates to circa 1760, the year T. Kitchin made a map of the Adirondack region and labeled northern New York “Cauchsachrage, an Indian Beaver Hunting Country.” Couchsachraga Peak was named by Bob Marshall, George Marshall, and Herb Clark, who made a first ascent on June 23, 1924. They initially called this 3,793-foot peak Cold River Mountain due to it standing above the Cold River.

Good Luck Lake

During the early 1800s, surveyor Lawrence Vrooman and party encountered this lake right after they passed by Spy Lake, which they named so because they “spied” it from the forest. At this second, then-unnamed lake, Vrooman’s son-in-law, John Burgess, shouldered his firearm, aimed it at a loon out on the water, and pulled the trigger. The firearm exploded, and everyone figured they would find Burgess missing his head once the smoke cleared. Miraculously, Burgess was unharmed. Thus it was rightfully named Good Luck Lake by his father-in-law.

Gothics

It’s a fine name and a rare singular name. The Reader’s Digest Great Encyclopedic Dictionary defines Gothic as: “Of or pertaining to a style of architecture much used in Europe, from 1200 to 1500, characterized by pointed arches, ribbed vaulting, flying buttresses, etc.” Gothics is a fitting name for this 4,734-foot mountain that possesses vertical rock faces, airy ridgelines, and an overall imposing appearance.

Hull Basin

Eli Hull, born March 26, 1764, was one of the first settlers of the Town of Keene, arriving in 1810 from Connecticut. He came with his wife, Sally Beckwith, a hardy woman who gave birth to 11 children of the wilderness. Eli lent his house, built in 1802, to hold the first church gatherings, and he opened one of the area’s first forges circa 1823. During the Revolutionary War, Eli journeyed to Gen. George Washington’s headquarters in Valley Forge but could not enlist in the military since he was too young. Washington was most accommodating to the patriot from the north. Hull became this officer’s servant until 1781 when he became old enough to enlist and fight in the war. Hull also fought in the War of 1812 and was in the Battle of Plattsburgh with three of his sons. Eli Hull died April 3, 1828, in the Town of Keene, where he’s buried.

Klondike Notch

Klondike Notch in 1895, 1953, and 1999. Note the Howard Mountain name change (United States Geological Survey)

While traveling into this notch on a cold winter day, deep snow hiding the forest floor and hemming your snowshoe tracks, it may not be difficult to think you’re in the real Klondike. The Klondike is an area, famous for a late 1800s gold rush, surrounding the Klondike River in Canada’s Northwest Territory and the Yukon district of Alaska. Klondike Notch, a name that dates to the late 1900s, is an example of a transfer name.

Lake Tear of the Clouds

When surveyor Verplanck Colvin and guide Bill Nye became first to reach this tiny pond on Sept. 16, 1872, the surveyor called it Summit Water. He described it in his 1873 state report as “a minute, unpretending tear of the clouds, as it were—a lonely pool, shivering in the breezes of the mountains, and sending its limpid surplus through Feldspar Brook to the Opalescent River, the well-spring of the Hudson.” From that sentence its current name bloomed, obscuring an earlier name of Perkins Lake. Colvin called the visit to this lake the “red-letter point” of his survey. Indeed. Prior to his and Nye’s visit, the source of the Hudson River was still undetermined.

Whiteface Mountain

This 4,865-foot mountain may be named for a large slide that occurred circa 1830. It was reported that a local man, “Uncle” Joe Estes, actually saw the landslide happen. This new slide left a swath of whitish bedrock, hence the name: Whiteface. However, the name Whiteface was in use before 1830. Uncle Joe has some explaining to do. Whiteface Mountain is likely named for an earlier slide, one that perhaps came down in 1806. Others feel this peak is named for its high elevation snowfields that last until June. Interestingly, this exact question regarding name origin—is it named from the slide or the snow?—exists for 4,020-foot Mount Whiteface in New Hampshire. No matter the name source, Whiteface Mountain was the first Adirondack High Peak to be named, this title first appearing in Horatio Spafford’s 1813 A Gazetteer of the State of New York.

This website contains affiliate links, which means The Trek may receive a percentage of any product or service you purchase using the links in the articles or advertisements. The buyer pays the same price as they would otherwise, and your purchase helps to support The Trek's ongoing goal to serve you quality backpacking advice and information. Thanks for your support!

To learn more, please visit the About This Site page.

Comments 1

Hi. Writing a book which includes the Wachocostinook Creek near Lions Head. Any knowledge of origin of the name Wachocstinook?

thanks. Greg