AT Resupply FAQs: Shopping Strategies, Nutrition Tips, and More

“So, are you going to have to hunt and forage your food?”

Virtually every thru-hiker has been asked this question. For people unfamiliar with thru-hiking, it seems logical. How else would you obtain food while living in the woods for five months? However, contrary to the initial belief of your friends and family, grocery stores and post offices do still exist near the Appalachian Trail.

Purchasing food on a thru-hike is often as simple as going to a store, but getting there from the trail—and getting foods that fit your unique needs as a hiker—can get complicated fast.

It’s worth figuring out how to resupply effectively on the AT: food is not only a significant chunk of a backpacker’s total pack weight, but also a source of emotional and physical resiliency on a grueling hike.

Everything You Always Wanted To Know About AT Resupply

Where can I buy food on the AT?

On-Trail Resupply

Does Every AT Trail Town Have a Grocery Store?

Repackaging Foods

Mail Drops

Can Mail Drops Save Me Money on Resupply?

Which AT Towns Should I Send Mail Drops To?

Disadvantages of the Mail Drop Strategy

What Foods Should I Buy?

What Is the Most Calorie-Dense Food for Backpacking?

Macronutrients: Maintaining a Balanced Diet

Micronutrients

Freeze-Dried Food vs. At-Home Dehydrator

Stove vs. Stoveless on the AT

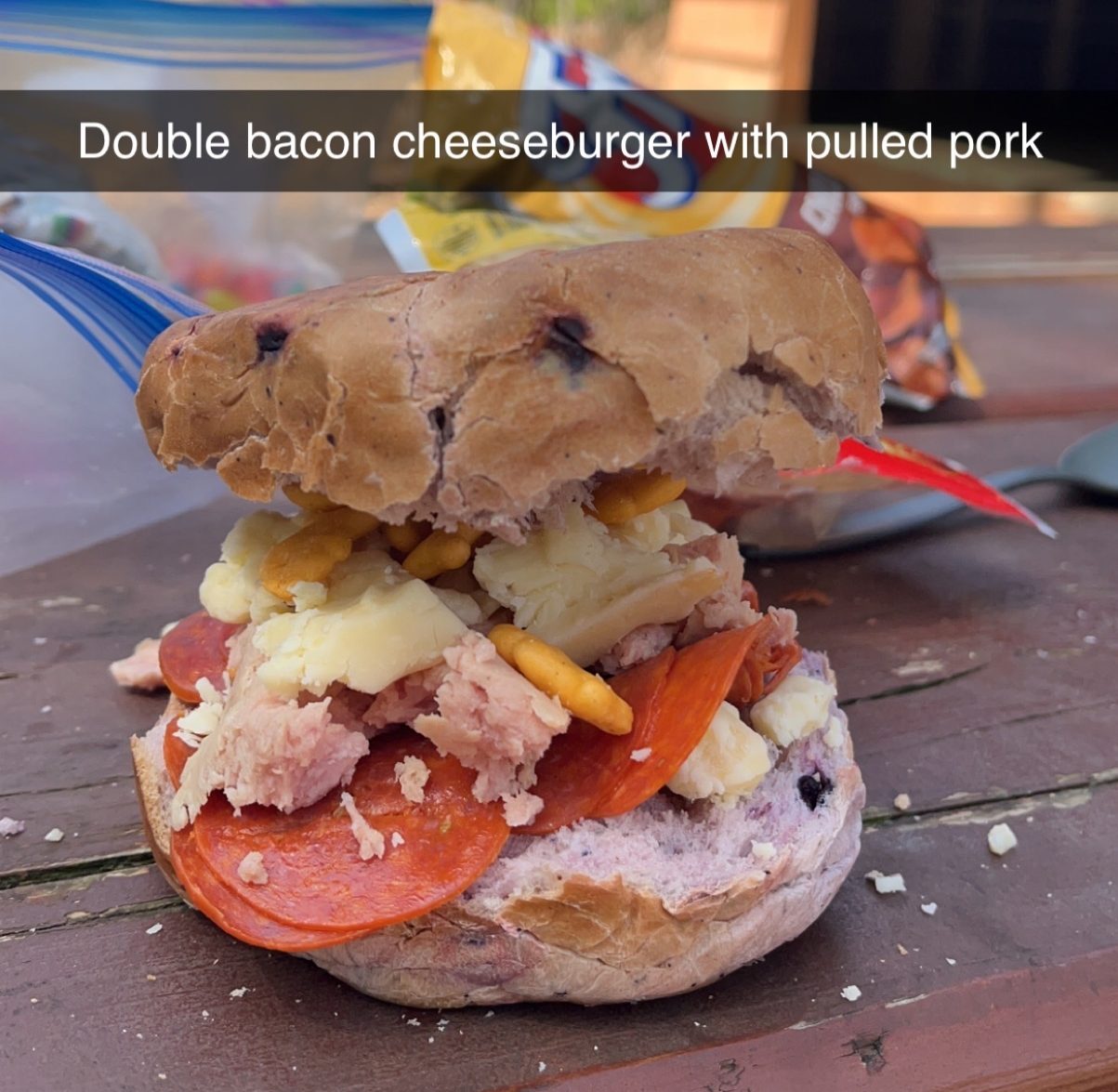

Thru-hikers are known for their creative meal choices, like this combination of mac and cheese, pepperoni, goldfish, Ritz crackers, and Combos.

Where do I purchase food?

When planning a thru-hike, you must decide whether to buy food locally along the trail or buy in advance and mail it to yourself as you go. The latter is referred to as a mail drop. Some hikers choose a combination of these strategies: buying groceries on the trail in some situations and sending mail drops to places with limited options for resupply.

On-Trail Resupply

The first step to buying groceries is getting to a store. In some cases, the AT passes directly through towns, but most of the time, you will need to hitchhike, shuttle, or take public transportation to reach town.

Hitchhiking is cheap and logistically easy, while shuttles cost money but are safer and more reliable. Public transportation is a great option when it is available, but most trail towns lack this service.

You have three options once you arrive in town: a zero day, a nero day, or a quick in and out.

Zero Day: During a zero day, you spend two nights in town at a local hostel or hotel, using the day in between to buy groceries, shower, do laundry, feast on restaurant food, and relax.

Nero Day: A nero day is a similar concept, except that you only stay in town for one night. You can a) arrive early and do your chores the day you arrive, or b) do them the second day and leave late. If you’re torn between enjoying your time in town and not splurging on two nights of lodging, you can do both by taking a nero!

In and Out: Hikers on a strict budget often prefer the in-and-out option. This is exactly what it sounds like: arrive in the morning, buy your groceries and do your chores, and leave the same day. No overnight stay. Though this is by far the cheapest option, it is not as relaxing or enjoyable as spending a night, and it is much more difficult to find somewhere to shower and do laundry without lodging.

Does every AT trail town have a grocery store?

Regardless of which strategy you use, your food-buying experience will vary based on the grocery options in each town. While many towns have large supermarkets or Walmarts, others only have small convenience stores, gas stations, or Dollar Generals.

Dollar General typically offers a modest selection of food for sale at reasonable prices. Most hikers won’t have any issues resupplying here, although you may have issues finding specific cravings. Convenience stores and gas stations can be hit or miss.

Stores near the trail may cater specifically to hikers and offer a better selection than your average shop, but plenty only offer classic gas station staples like snacks, candy, and beverages. When planning a resupply, check FarOut for the most accurate information about the quality of these stores.

READ NEXT – A Detailed List of Appalachian Trail Resupply Points

Help! I can’t get my resupply to fit in my backpack!

Before getting back on the trail, it’s helpful to repackage your food. Boxes and large plastic bags take up significant space in a backpack, resulting in lots of bulky trash to carry with you to the next town.

By transferring food from its original package into Ziploc bags, you’ll save significant weight and space. This process of repackaging can easily take upwards of half an hour and underscores how much waste goes into food wrappers.

Mail Drops

Some thru-hikers prefer buying food in bulk ahead of time, then mailing it to themselves as they go. The mail drop strategy avoids the inconsistency and high prices of trail town food stores. It also allows picky eaters and those with dietary restrictions more options and peace of mind, saving them from worrying about whether the 7-Eleven will have four days’ worth of gluten-free food, for example.

Is sending mail drops cheaper than resupplying along the way?

One potential advantage of sending yourself mail drops is that when planned well, it can be cheaper than buying food on-trail at small-town convenience store prices, even after factoring in the increased shipping cost. You can go to a budget hometown grocery store or warehouse store like Costco and buy tons of food in bulk. Then, divide the food into segments of about four days (or however long you plan on going between resupplies), and package it up.

USPS flat-rate shipping is often the cheapest way to send mail drops to the AT. A large flat-rate box currently costs $23 at the post office—so if your primary goal is to save money by sending mail drops, you need to save more than $23 on the contents of every box you send compared to what you would pay on-trail.

That’s easy to do when comparing to food prices in some pricey AT trail towns (looking at you, Fontana Dam), but you’ll need to be an expert bargain shopper for your mail drop to beat out Walmart prices in (for instance) Marion, VA.

Pro tip: Box, but don’t seal, your packages before hitting the trail. By leaving the boxes open, your at-home mail drop coordinator can throw in last-minute goodies and necessities at your request before shipping each one.

Where should I mail my resupply boxes?

While nothing is stopping you from making a detailed mail drop schedule, the wild inconsistency of the trail will almost certainly throw these plans to the wolves. It’s better to leave the boxes with a friend or family member and update them periodically on where and when to ship them.

But how and where do you ship them? Appalachian Trail Mile 1,246.3 isn’t exactly a valid shipping address. The most widespread options are post offices and hostels.

Post offices in trail towns are used to hikers and are usually very reliable. However, they often have very limited hours. It can be soul-crushing to show up to a post office on a Friday afternoon, only to find out they are only open from 9:30 to 11 AM Monday through Friday and closed for full moons.

Hostels are a better option as they are open at virtually any daylight hour, though you will usually need to spend a night there or pay a fee for holding your package. Call ahead to get permission before sending a box to a hostel, as some have limited storage space or specific instructions for labeling packages.

Disadvantages of the Mail Drop Strategy

The mail drop strategy sounds awesome on paper. It gives you more food options and might save you money. So why did only 5 percent of hikers exclusively use this strategy, according to The Trek’s 2022 Thru-Hiker Survey? As it turns out, mail drops force you to sacrifice a lot of flexibility. They hold you hostage to the postal service, requiring you to be at certain places at specific times to pick up your packages.

Furthermore, it’s tricky to gauge how much and what types of food you’ll want to eat on trail. Months of Knorr Pasta Sides or ramen noodles can quickly become unappealing. Granola bars sound like a safe bet in theory, but it’s impossible to predict whether you’ll want them three months from now. Maybe by then, you’ll have an insatiable craving for Fritos and Twinkies.

There’s also the chance that you’ll send too much or too little food, forcing you to waste money by either offloading precious snacks to the hiker box or buying extra in town anyway.

Perhaps the perfect solution for those having a tough time deciding is a mix of both. Most trail towns have a decent resupply option, so only sending yourself packages in remote areas without good options makes a lot of sense. Many hikers send boxes to towns with limited resupply options, like Fontana, NC, Harper’s Ferry, WV, and Monson, ME, and plan to grocery shop in towns that boast a Walmart Supercenter or Food Lion.

READ NEXT – 6 Trail Foods That Never Bore Me (No Matter How Much I Eat)

What food should I buy for thru-hiking the AT?

After choosing a strategy for resupplying, you will be faced with an obvious question: What food should I buy? The answer depends on a lot of factors. What are your nutritional needs? How does hiking all day every day affect the number of calories you need? What about the weight of the food? Are you carrying a stove? The answers to these questions depend on the person, so let’s dive in.

It’s very important to note that everybody is different, and what works for your friend or tramily may not work for you. S oake the nutritional advice in this article with a grain of salt (figuratively and literally—it’ll give you electrolytes).

What are the most calorie-dense foods?

Unfortunately, consuming a lot of calories comes at a price. Not just financially but also in terms of pack weight. Hikers want to maximize their calorie intake while minimizing the weight of their food. This is where caloric density comes into play. Measured in calories per ounce, this is the best way to measure how efficiently you are carrying your food.

Look for foods that pack at least 100 to 120 calories per ounce—the higher the better. As a rule of thumb, plan for each day’s food to weigh between 2 and 2.5 pounds.

Fats: Fatty foods tend to be the most calorie-dense: one gram of fat provides nine calories, while the same amount of protein or carbohydrates provides only four calories.

Olive oil, which is very fatty, is the most calorie-dense food out there at a whopping 235 calories per ounce. Some thru-hikers (myself included) even take shots of pure olive oil to meet our bodies’ high demands for calories. You don’t need to take it to that extreme, though. Other calorie-dense foods that are popular with thru-hikers include walnuts (173 cal/oz), peanut butter (168 cal/oz), Fritos (160 cal/oz), and Nutella (153 cal/oz).

Macronutrients: Maintaining a Balanced Diet On-Trail

While fatty foods have awesome caloric density, a diet made up primarily of fat can be a nutritional nightmare. It’s easy to think that you can eat whatever you want on trail, but when you’re physically exerting yourself all day, every day, balanced nutrition becomes even more important. Make sure you’re getting a mix of all three macronutrients: not just fats, but also carbohydrates and protein.

Carbs: A thru-hiker also needs a lot of carbohydrates, the body’s primary source of energy. During digestion, carbs get broken down into glucose, which the body uses as fuel, and glycogen, which is stored in the liver and muscles and can be converted into energy later. Nutritionists recommend that about half of a thru-hiker’s diet should come from carbohydrates. Pop Tarts, pasta, and rice are popular among thru-hikers due to their high density and low cost.

Protein: Finally, after exhausting your carbohydrate and fat reserves, your body will turn to breaking down proteins for energy by sacrificing some of your muscle tissue. This is a bad situation. Losing weight is OK and is to be expected on a thru-hike, but your body needs enough carbohydrates and fats in order to prevent your body from eating its own muscles.

It also needs enough protein to replenish any muscle tissue that is burnt. Good options for proteins include nuts, cheese, canned meat like SPAM or tuna, and pre-cooked meat like chicken packets, jerky, or bacon.

Micronutrients

Micronutrients are also crucial. Without the proper vitamins and minerals, you can experience problems like fatigue, a weakened immune system, and cramping. In the everyday world, most people get a large portion of these micronutrients from fresh foods like fruits and vegetables.

Unfortunately, these are some of the least calorically dense foods because they are mostly water. Apples and blueberries contain about 16 calories/oz, watermelon is 8 calories/oz, and lettuce comes in at just 4 calories/oz.

Hikers seeking a balance between pack weight and nutrition sometimes pack fresh produce for the first day out of town only and make up for the deficit of healthful foods by loading up on fruits and veggies when eating in town. The rest of the time, freeze-dried and dehydrated produce helps fill the gap.

Freeze-Dried Backpacking Food vs. At-Home Dehydrator

Again, the low caloric density of fruits and vegetables has to do with their water content. Water is heavy and contains zero calories, so thru-hikers prefer dehydrated foods. Thankfully, there are plenty of options at most grocery stores, like dried fruits (which usually contain 60-80 calories/oz).

Some hikers take it a step further and prepare their own backpacking food using a food dehydrator. These can dehydrate just about anything, from simple fruits and veggies to full meals.

If you want dehydrated meals without putting in the effort of using a dehydrator, there is a plethora of brands that specialize in freeze-dried backpacking meals, like Mountain House and Backpacker’s Pantry.

While delicious and relatively nutritious, they are rather expensive at $10–$15 per meal, which adds up quickly over a span of months. Most thru-hikers forgo these premade meals due to the cost, but bargain hunters can usually find some on sale at Walmart or Sierra.

READ NEXT – How To Lower Your Base Weight Without Replacing the Big Three

Should I Carry a Stove?

A typical set of cookware includes a stove, fuel canister, and pot. Pictured: MSR PocketRocket Deluxe Stove Kit.

Stove

An important question to ask yourself that will affect the kinds of food you buy and your hiking experience is whether or not you want to carry a stove. A stove opens a world of opportunity, allowing you to cook hot meals that would not be possible without one. However, stoves add weight and require fuel, making your pack even heavier.

Despite the added weight, many thru-hikers swear by their stoves. A hot meal after a grueling day of hiking is rewarding and provides something to look forward to. It’s a great way to warm up on a cold day in spring or fall. Knorr Pasta and Rice Sides, ramen noodles, and instant mashed potatoes are very popular because they’re inexpensive, widely available, and provide a lot of calories compared to their weight.

Stoveless

Other thru-hikers forgo the stove and use other methods of preparing food. One popular method is cold soaking: the process of filling a plastic bag or jar with a dehydrated food like pasta, adding water, and waiting for a number of hours until the water is absorbed. Usually, hikers will do this in the morning for it to be ready by dinnertime. This allows stoveless hikers to eat dehydrated foods, but it also requires them to carry more water weight throughout the day.

Another strategy is to go stoveless but not cold soak. In this case, your dinners will often consist of sandwiches, tortillas, and snack food. This is a great way to save money and potentially weight, though the flavor and nutritional value of your meals will likely suffer.

It’s important to note that bread and raw foods often aren’t as calorie-dense as dehydrated and freeze-dried options, so you may make up the weight you saved by forgoing the stove by having to carry heavier foods.

READ NEXT – 6 Easy Cold Soak Recipes for Your Next Thru-Hike (Basic Ingredients Only)

If you’re unsure about whether or not going stoveless is right for you, keep in mind that The Trek’s 2022 Thru-Hiker Survey found that just 9 percent chose to go this route. Carrying a stove is by far the more popular option, and a whopping 93 percent of hikers surveyed were happy with their choice of stove.

Conclusion

When preparing for a thru-hike, people tend to obsess over the three heaviest gear items, known as the Big Three: the backpack, tent, and sleeping bag. These gear choices are incredibly important, but they’re not the only things that impact your pack weight and the quality of your hike. Like the Big Three, your choice of food can also make or break your trek in a very significant way.

In reality, the single heaviest item in most people’s packs is actually their food bag. Choosing the right food is the easiest way to cut down weight, save money, and ensure that you have the energy to hike over 2,000 miles. If you are setting out on a long-distance hike, be sure that you don’t overlook this critical consideration.

Featured image: Photo via Reptar; graphic design by Zack Goldmann.

This website contains affiliate links, which means The Trek may receive a percentage of any product or service you purchase using the links in the articles or advertisements. The buyer pays the same price as they would otherwise, and your purchase helps to support The Trek's ongoing goal to serve you quality backpacking advice and information. Thanks for your support!

To learn more, please visit the About This Site page.

">

">

Comments 8

Slurpee! It’s Blacklight. I thought, I recognized that giant green food bag. Good articles! Juat read all of them. Hope you are well!

I’ll be on the AT again tomorow 4/16 & the CDT after for 2023.

I’ve had great success shipping all my food for the ECT, AT & PCT. To give an exact cost to do a thruhike for using only mail drops: My total cost for 210 days food/supplements and 5300 miles for 2023 is 8.50 per day. That does not include shipping costs. I also prebuy and ship all my shoes/socks so 10 pair.

It takes a ton of work to prep and research the places you want to ship to but it also saves a ton of time in towns. No more shopping etc.

Happy trails!

I found it very helpful to send a “Bounce Box”.

I would mail it via USPS to the next town up the trail that was on the trail or very close to the trail.

That wound up being about every 100 miles and cost about $20 for a fairly large box.

In the box, I would put things I ‘might’ need. Things I don’t want to carry. Things that people say they “shipped home”.

Maybe grooming things like toenail clippers, hair clippers, spare parts, back up clothing, etc. Anything I would normally use at home.

A bounce box is generally your “hiker junk drawer”.

And if there was some food I liked, but was hard to find (like ProMeal peanut butter).

Grocery stores on the AT are pretty well stocked with hiker type foods, so I wouldn’t bother shipping things like Knorr meals.

Great post that answered a lot of questions. With the potentially “crappy” diet of a high school student does taking a daily multivitamin help?

I will remember the hint regarding full moon closures and consult my lunar calendar when planning. Glad to hear my power napping skills qualify as a “sport”.

Really great summary … thank you!