The Top Backpacks on the Appalachian Trail: 2016 AT Thru-Hiker Survey

Unless you’re making the rest of us jealous by slackpacking the whole way, your backpack is one of the most important pieces of gear you take on a long-distance hike. Whether you come to hate it or you come to feel like it’s a part of your body, it’s critical to wear the right pack for your body size and the weight you’re carrying.

Like we did last year, Appalachian Trials surveyed long-distance hikers about their backpack choices. In addition this year, we also asked about the load hikers carried and the items they “shook down.” If you don’t want the details, I’m offended (just kidding – you can skip to the TL;DR at the bottom).

Related reading: 2017’s Best Backpacks for Thru-Hiking

The hikers

For details on hiker demographics, check out the post with an overview of general information from the 2016 survey. One hundred fifty people who hiked the Appalachian Trail in 2016 provided information about their backpacks, so not all hikers in the total sample were included in the analysis for this post.

For the backpack sample, the median age of hikers who took the survey was 28 years old. Half of all hikers (50%) were in their twenties. A little over half (56.7%) of hikers who took the survey were men; slightly less than half (42.7%) were women.

Three quarters of hikers in the survey (75.3%) were thru-hikers or had walked over 2,000 miles in 2016; a quarter of them (24.7%) were section hikers. There were no age or gender differences between section hikers and thru-hikers.1

Most hikers had done backpacking trips just a few days long, prior to their thru-hikes. Extensive experience and utter lack of experience were both uncommon.

The typical backpack

About one in five hikers (21.3%) switched out backpacks at some point. About 15% replaced their pack with another one of the same model, while about 7% switched to a different model (more on this later).

Regarding the primary pack that hikers used, 84.7% were internal frame packs, 7.3% were frameless, and 6.7% had traditional external frames.

The two backpacks counted as “other” were because one hiker used an ultralight, external frame pack, and one removed the frame from his pack.

Backpacks ranged in capacity from 30 liters to 80 liters. The average capacity was 57 liters, plus or minus 9 liters.

Base Weight

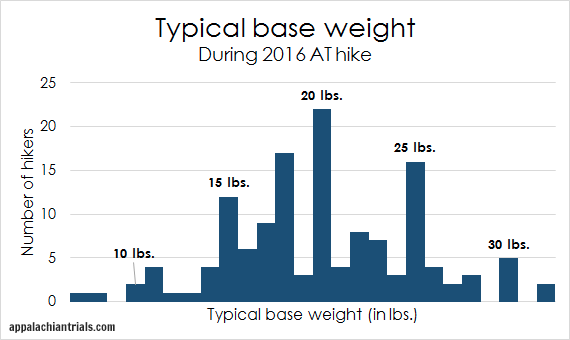

“Base weight” refers to how much a backpack weighs when it is filled with everything except food and water. This often fluctuates during a long-distance hike, but it is more stable than total pack weight with food and water. Hikers in our survey reported the typical base weight during their 2016 AT hike. Their average base weight was 20 lbs., plus or minus 5 lbs.2 Base weights ranged from 7 lbs. to 32 lbs.

The average base weight for section hikers was 22 lbs., while the thru-hiker average base weight was 19 lbs. Furthermore, there was a slight association between distance hiked and base weight, meaning hikers with lower base weights were more likely to have walked further.3 This could be because thru-hikers “shook down” their packs more, invested more money in lighter gear, or it could be that a lower base weight helped people stick with it.

Problems with weight and capacity

Base weight and backpack capacity were related, meaning that people with a heavier base weight were more likely to be using larger capacity packs, most of the time.4 However, surprisingly, hikers with frameless packs were no more likely than other hikers to have lower base weights.5 This means that, despite carrying ultralight packs or extra large packs, many hikers in our survey were still carrying the same weight as hikers with standard packs.

In fact, in the comments they provided, fifteen people (10%) said their packs were too big or heavy in proportion to the load they carried, while five people (3.3%) said their packs were too small and light in proportion to the load they carried. Two hikers said their low-capacity pack helped to keep them from carrying too much.

So, long-distance hikers on the AT in 2016 were roughly carrying loads proportionate to their pack capacity, although many were carrying ultralight frameless packs filled with a more-than-ultralight load. The real question is, does that actually pose a problem?

Apparently, it does. We found that type of frame, backpack capacity, and distance hiked didn’t contribute to hiker satisfaction with their backpacks. However, hikers with more experience backpacking and those with a lower base weight were more satisfied with their backpacks.6

This means that, while hikers may have attributed the quality and comfort to the backpack itself, the weight of the load inside it is really what affects satisfaction. Of course, the relationship between hiker experience and satisfaction basically means the more practice you get, the more you’ll narrow down what works for you.

Top Brands & Models7

Most hikers were at least somewhat satisfied with their packs, and no particular brand was disproportionately problematic. Still, when we asked hikers the brand of their favorite pack they used. Here are the results:

Most Popular Pack Brands

We also broke down the most popular backpacks, by model or series.

Most Popular Pack Models

- Osprey Exos

- Osprey Aura

- ULA Circuit

- Osprey Atmos

- Z-Packs ArcBlast (tie)

- Gossamer Gear Mariposa (tie)

The most popular backpack model or series was the Osprey Exos, which is a unisex backpack built for a typical load (20-40 lbs. total, so a base weight of around 15-30 lbs).

The most popular pack specifically designed for men was the Osprey Atmos, a similar size pack.

The most popular women’s pack was the Osprey Aura, which is also a standard-capacity internal frame pack. The Gregory Deva was also a popular standard-capacity women’s pack.

The most popular lightweight pack (for a base weight around 15 lbs.) was the ULA Circuit, followed by Zpacks’ Arc Blast.

Backpack repair and replacement

As mentioned earlier, 21.3 % of hikers replaced their backpacks at some point. Compared to sleeping bags and footwear, this is a relatively small number of hikers replacing their packs.

In their open-ended comments, 14 hikers in the survey (9%) said they had at least 1 pack fall apart or break. In all 14 cases, the gear company replaced or repaired the packs free of charge.

Shakedown and “shakeup”

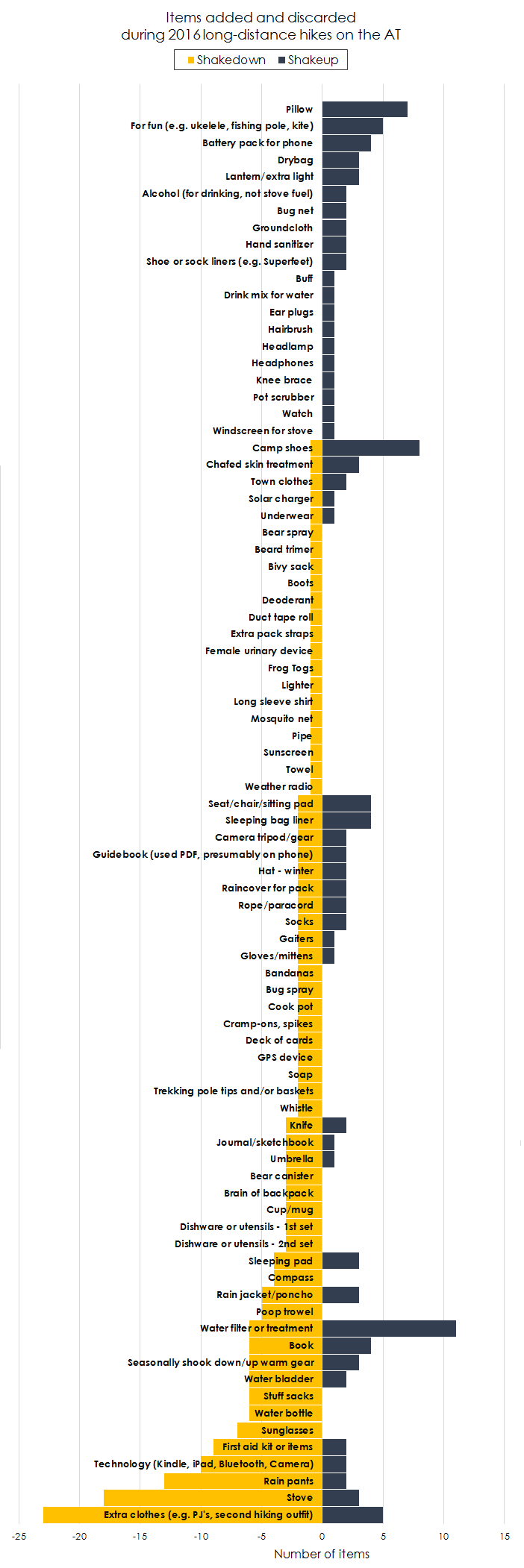

Considering the role of base weight in hikers’ satisfaction with their backpacks, it’s also relevant to see what items hikers discarded during their hike (i.e., a shakedown) and what they decided to bring with them (what I’m calling “shakeup”).

We didn’t get a comprehensive list of the items hikers brought the entire way, but we did see what items hikers discarded or eventually added to their packs.

Some items were commonly added AND removed, like water treatment and pack covers. Some items, like stoves, were high on the shakedown list, although most hikers probably bring them the whole way. Other items, such as pillows, were high on the shakeup list, although most long-distance hikers do not bring them. So, the utility of the chart is limited, but it could be useful if you’re on the fence about bringing something. Similarly, it could provide you with ideas if you really need to lower your pack weight.

TL;DR

- Most likely, one backpack will last you a full thru-hike. And if it breaks, you can get a free replacement, so don’t worry about budgeting for more than 1 pack.

- For inexperienced backpackers, know that the more practice you can get, the more likely you won’t have problems with your pack. For practice hikes, make sure to fill it with the amount of weight you anticipate carrying.

- Again, for inexperienced backpackers, aim for a base weight of about 20 lbs, plus or minus 5 lbs. This was the typical base weight for most thru-hikers and long-distance section hikers.

- If your base weight is 20 lbs or higher, make sure to use a standard pack. A minimalist or ultralight pack will not be your friend. This may seem obvious, but considering how many people used packs that were not designed to carry such a heavy load, it’s worth saying again.

- If your base weight is higher than 20 lbs. and your pack feels uncomfortable, keep in mind that the load, not the backpack itself, is most likely the problem. Try shaking down your pack rather than replacing it.

- If you’re unsure what to shake down, the items on the chart above might be a good place to start. In particular, extra sets of clothing or special clothes for sleeping in are probably redundant.

- Support cottage industries and small businesses when you can! But if you don’t know where to start regarding a pack to buy, try one of the common brands/models shown above: the Osprey Exos for a standard pack, the Osprey Aura for a women’s pack, and the ULA Circuit for a lightweight pack.

Thank you!

Many thanks to all the hikers who participated in the survey! Congratulations for walking so far! Also, many thanks to Zach Davis for his input on this survey and for getting the word out.

More AT gear “By the Numbers”

Check out the overview post for this years’ survey and the post on footwear. Up next will be sleeping bags, pads, shelter systems, and food/cookware. For now, check out last years’ posts on shelter systems, sleeping bags, and sleeping pads.

Notes for the Nerds

- Bivariate Pearson correlation with age and distance hiked was not significant (r = -.122; p = .139). Chi-square between sex and distance hiked was not significant (X2 = .349; p = .840).

- “+/-” refers to standard deviation from the mean.

- Bivariate Pearson correlation showed a weak but significant correlation between distance hiked and base weight (r = -.184; p = .026).

- Bivariate Pearson correlation showed a moderate, significant correlation between base weight and pack capacity (r = .350, p < .001).

- Bivariate Pearson correlation showed the correlation between pack type and base weight was non-significant (r = .093, p = .267).

- Satisfaction with primary backpack used was substantially negatively skewed (skew = -1.68), so this variable was Log10 transformed. A linear regression was conducted to predict satisfaction. Prior experience significantly predicted backpack satisfaction (β = -.023, t (145) = -3.24, p = .002). Likewise, base weight significantly predicted backpack satisfaction (β = -.182, t (145) = -2.103, p = .037). Together, prior experience and base weight explained 12.9 percent of the variance in backpack satisfaction (R2 = .129, F(4,135) = 4.99, p = .001).

- I have not been paid by any gear company, nor do I have any other reason to endorse one.

This website contains affiliate links, which means The Trek may receive a percentage of any product or service you purchase using the links in the articles or advertisements. The buyer pays the same price as they would otherwise, and your purchase helps to support The Trek's ongoing goal to serve you quality backpacking advice and information. Thanks for your support!

To learn more, please visit the About This Site page.

Comments 12

I hiked 2015 with a Gregory Deva that fell apart, and Gregory did not replace my pack. They did not even give me the option to send it in for repairs (they would not accept it if it were “dirty or malodorous” – and this after 1200 miles of me sweating into it). I tell all future hikers to avoid Gregory for this reason.

It is interesting that/how the class of backpack dominance has changed over the years. During my thru-hike ’78-’79, the dominant class was overwhelmingly the external frame, with Kelty & Jansport as the big 2 brands. The Kelty Tioga and Tioga Junior were probably the most popular among NOBOs (which wasn’t a term back then). I used a Jansport D2 (top capacity), and my buddy used a Jansport D3 (a little bit less capacity). Our packs were big because we were SOBO and in cold weather. With my 1st shakedown at Gorham, and 2nd at Hot Springs, I switched to a small summer Jansport external frame, model unrecalled. External frame advantages: They are highly adjustable, they have great ventilation, at the time they were less tech and so less expensive than the internal frames packs. Internal frames were/are less restrictive to movement, so more maneuverable on a scramble and especially on a bushwhack than external frame packs. However, the AT is the hikers super-highway. The vast majority of the time, the hiker is trudging along and upright. At least that was how it was.

I find it interesting that, according to the Halfway Anywhere survey, the AT base weight is way higher than on the PCT. Anyone have any theories on why that is?

Fireman I only met one PCT thru-hiker doing the AT whereas I’d guess that a lot of PCT hikers are AT veterans (that possibly makes them more likely to be part of the online community and therefore be the ones coming across and doing the surveys). Upgrades to a hiker’s gear between trails will almost certainly revolve around reducing weight and their experience and planning will lead to a much reduced base.

According to the survey only 27% of 2015 PCT thruhikers had done a long distance hiker before so that shouldnt affect the average that much even if they did the AT before. What was your baseweight on the AT?

I think for next year they should ask for starting baseweight and ending baseweight.

Yes that would be a better question. Mine started mid 20s and finished just over 20.

The only other reason I can think of is that there’s a weighing station at the approach trail where some of the AT Nobos start as well as the pack shakedown outfitters in Georgia so people are more likely to have weighed their kit at the start and remembered that figure before they discarded their stuff?

I don’t know that much about the PCT so could be completely wrong but I guess if you’re starting in the desert you’re not carrying the cold weather gear that the Feb/March AT Nobos (a fair chunk of those surveyed: https://photos.thetrek.co/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Graph-start-date-2.png ) are carrying.

Or maybe we just have to admit the West Coast does it better!

Thanks for the research. It encourages me to downsize on my next long hike.

As far as the AT/PCT dichotomy, my impression is that the entire mindset is shifted somewhat more to lighter weight, longer distance. This is, I think, somewhat in response to the trails themselves. A successful PCT thru demands longer distances than the AT, but the drier climate on the southern half of the PCT encourages lower weights for shelter and clothing. Ray Jardin’s influence was felt earlier and more strongly out west.

Maybe it is just me but I really don’t understand the shakedown/shakeup chart. I think that shakedown means what they ended up dropping while on the trail and shakeup means what they added while on the trail or what they started with? I am confused. And how does season changes relate to dropping or adding? Thanks!

Probably the most thorough analysis of any backpacking gear & hikers I have read. Nicely done.

PS, liked the statistical analysis.

Love the article because I love these statistics 🙂 Thank you!

your surveys are very, very valuable. i am 66 years old. a few like-aged friends and i plan on tackling a 100-mile section in late spring/early summer in 2018.

thank you much.

paul

Hi there, of course this article is really pleasant and I have learned lot

of things from it about blogging. thanks.